|

"Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, and welcome to the celebration of the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park. With the eyes of the baseball world upon our home, which John Updike once called a lyric little bandbox of a ballpark, this afternoon our old friend celebrates its 100th birthday. It was 100 years ago on this very day, at this very hour, on this very field, that the Boston Red Sox were preparing to play Fenway Park's first major league game against the New York Highlanders, who one day became the New York Yankees." "We are all connected to that first game through generations of shared emotions: through the squeeze of a pop up that clinched the Impossible Dream ... The joy of a Game #6 home run that clanked off the left-field pole ... The heartbreak of a home run that tucked itself behind the "Green Monster" ... And the suspense of a Game #4 steal with our backs to the wall." "To paraphrase the beautiful language from the movie "Field of Dreams" ... The one constant through all the years has been baseball, and the one constant in baseball has been Fenway Park. Ballparks have rolled by like an army of steam rollers. They've been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But Fenway Park has marked the time. The field, this park is a part of our past. It reminds us all of what once was good - so good - and could be again." ... Carl Beane, Red Sox public address announcer, April 20, 2012

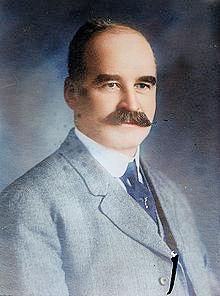

The American League began operations in 1901 with eight charter franchises and an announcement on January 28th of that year. The team that would later become known as the Red Sox was officially inducted into the league and the city. American League president, Ban Johnson had created the league, and fully intended to compete with the only other major league, at the time, the National League. One of his keys was to place a franchise in Boston virtually next door to the existing National League team, as one of his flagships. Suitable land to build a ballpark was owned by the Boston Elevated Railroad on the south side of Huntington Avenue. The plot was located at the intersection of Huntington Avenue and Rogers (present day Forsyth) Street and was in the same neighborhood, but on the other side of the railroad tracks, as the South End Grounds (1871-1915), home of the National League team. The land was purchased by Charles Somers, a wealthy Cleveland businessman and Johnson crony who, at the time of the purchase, was a part owner in the Cleveland franchise in addition to his title of American League Vice President. Digging into his deep pockets, Somers had lent money to Connie Mack and Ben Shibe to establish a team in Philadelphia, PA and loaned money to Charles Comiskey so that he could expand the ballpark in which the Chicago White Sox were playing. Finally, he stepped in as owner of the new Boston Americans franchise when no local owner could be found, relinquishing his interest in Cleveland's team. He made Boston into a powerhouse by luring away star third baseman Jimmy Collins from the National League's Boston Beaneaters and pitcher Cy Young from the St. Louis Cardinals. This commitment to the circuit's success made Somers a key person, and he was rewarded with the league's vice-presidency. In 1902, he was able to sell his interest in the Boston franchise to Henry Killilea, and went back to running his hometown team.

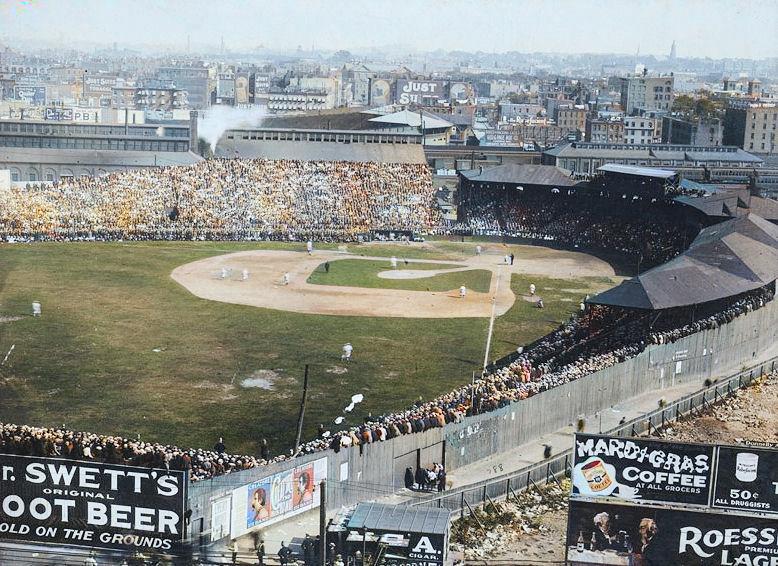

When it was completed, the ballpark dubbed Huntington Avenue Grounds, seated 9,000 fans, with room for thousands more standing behind ropes in the outfield and the ample foul territory, where 90 feet separated the stands from the diamond. The wood-framed Huntington Avenue Grounds proved to be a success for the first-year franchise in the new league, as estimates placed between 289,000 and 322,000 fans through the sole turnstile, twice as many paid admissions garnered by the previously established Boston National League team. While the "Nationals" (later called the Braves) charged 50 cents for admission, the "Americans" charged only 25 cents for a grandstand seat. With the lower price and a combination of a good ball club and a new spacious park, the stage was set. The team was still six years away from being called the Red Sox (1908). Nor were they the Puritans, the Pilgrims, or the Somersets (after Charles Somers), which some sloppy historians have called them. These were merely nicknames coined by sportswriters, who as a class never met a synonym they didn’t like. Newspapers most often referred to the team as the Americans, to differentiate them from Boston’s National League club.

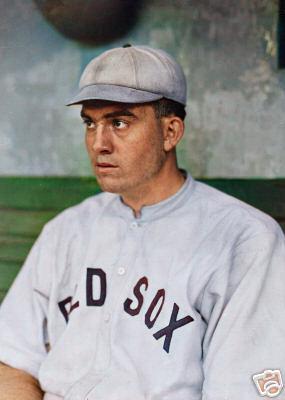

In 1903, Boston won its first American League pennant and the first World Series. By then the Boston Nationals didn’t matter anymore. Boston was an American League town. With a successful franchise and championship under his belt Ban Johnson set out to build up the team in New York. It was time to sell the Boston team. With the team’s success, Civil War hero and Boston Globe publisher, General Charles Taylor thought it a good family investment. He put up $135,00 and bought the club. He installed his Son, John I. Taylor as the club’s president. The club continued to have success although Taylor had no idea what he was doing. It was player-manager Jimmy Collins who ran the team, while Taylor just signed the checks. As the decade closed, the club slipped down in the standings and The Huntington Avenue Grounds became just a pleasant place to go and spend an afternoon. Taylor knew he had to restock his team. Traditionally most ballplayers had come from New England and the northeast, which is where baseball was most popular. But as professional baseball spread, there was a growing demand for young players. Taylor decided to head west to find new talent. The first major signing by Taylor was a young Texan named Tris Speaker. In 1909, Speaker earned a starting position in Boston’s outfield. Californian Harry Hooper soon came to the team along with a young Kansas native named Joe Wood. In 1911, Californian Charley Hall joined the team along with outfielder Duffy Lewis. They joined New Englanders Buck O'Brien, Bill “Rough” Carrigan, Ray Collins and Larry Gardner.

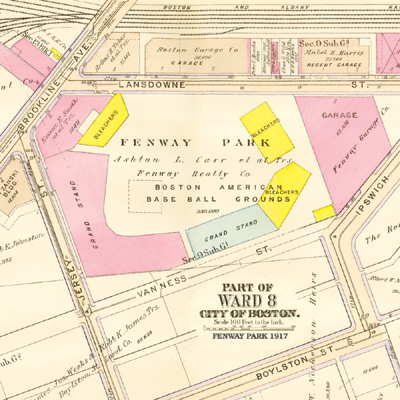

In 1911, Taylor was now ready to extricate himself from the daily operations of the team. That year, Ban Johnson made it clear that his American League franchise must build new safe ballparks with fireproof stands built of steel and concrete. These building materials were safer, but also could support the weight for larger grandstands and more seating. Huntington Avenue Grounds could only seat 9000 fans and on many days 5000 more would show up and be forced to stand around the field. Many potential speculators therefore refused to submit offers for the Red Sox organization. Between 1881 and 1885, the designer of Central Park in New York City, Frederick Law Olmsted, created what was called the "Emerald Necklace" of parks surrounding Boston. The marshland between Muddy River and Stony Brook became the last of Boston's landfill areas. It was drained, filled in, and became known as "The Fenway". The Fenway Park side of Landsowne Street was really “the other side of the tracks”, dividing the affluent Back Bay from the South End section of the city where The Huntington Avenue Grounds was located. The site was on the edge of what had been a mud flat, occasionally flooding. Since then it had sat there undeveloped, being used as a dumping area for neighborhood trash.

The Taylors still placed some conditions on their willingness to build a new ballpark. Firstly, the did not want to go into debt to finance the construction. Secondly, they needed the surrounding area to be commercialized. The Taylor family not only owned the Red Sox, but also the Boston Globe and The Fenway Realty Company. So, as part of a shrewd real estate venture, they acquired this tract of land known as the “Dana Lands” at public auction for $120,000. So John Taylor sold himself some of this property surrounding "The Fenway" area near the newly expanded streetcar line that fed Kenmore Square, and bordering the recently developed Boston and Albany Railroad behind Lansdowne Street.

Taylor owned the Huntington Avenue Grounds, but he had to lease the land from the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. Now he could build the ballpark and own the land, which he would rent out to the new ownership, ensuring a financial windfall for years to come. This land and a new modern ballpark to be built on it, would greatly increase the team's value. Furthermore, to draw attention to the surrounding real estate that he controlled, would name the new ballpark "Fenway Park".

In June, the Taylors announced their intention to build a new and large spacious ballpark. Naturally, Ban Johnson had some of his personal friends lined up as potential buyers. James McAleer was one of Johnson’s trusted confidants and business associates but he needed Johnson to line up the additional investors. Johnson and McAleer brought these investors to Boston at the end of the 1911 season for a series of meetings with Taylor.

Taylor brought in the architect, James McLaughlin, to design Fenway Park. McLaughlin became notable having designed many of Boston’s public buildings and schools as the conversion from wood to concrete was being widely adopted, in an attempt to keep the public safer from the threat of fire. McLaughlin gave the presentation and showed the plans for the new ballpark. The investors were impressed. Blueprints for the park showed that it would accommodate 24,400 patrons. Fenway Park’s concrete and steel grandstand stopped just past third base and first base. And, although the structure was designed to hold the weight of an upper deck, Taylor decided to not go that route to save money. He was not interested in grand plans and wanted no frills. After all, he was trying to sell his investment. The plan spelled profit pure and simple. A few days later on September 15th, Taylor sold the Red Sox to McAleer and his investors for $150,000. Although he would no longer own the team, he kept ownership of the park. The Taylor’s original investment had doubled. Groundbreaking took place on September 25, 1911. There was no ceremony, no speeches, no ribbon-cutting. With opening day only five months away, there was a lot of work to be done. On October 7th, the Red Sox played at The Huntington Avenue Grounds for the last time. It was “Kids Day” and as the day ended so did an era. James McLaughlin hired the Charles Logue Construction Company as the general contractor and built Fenway Park at a cost of $650,000.

The outside red brick facade, was designed in a tapestry style, to give the outside, a New England sampler appearance, and blending in with the surrounding neighborhood at the time. Inside, the central grandstand was built of steel and concrete and the seats were made of oak. Season tickets for a box (which consisted of four seats) cost $250. There was a right field pavilion which had wooden seats on a concrete foundation. The left field grandstand and the bleachers in right and center field were constructed in wood. In total, there were 15,000 reserved central grandstand seats and 13,000 unreserved grandstand and bleacher seats. Later, a new grandstand in deep right field, between the right field bleachers and right field pavilion was built for the 1912 World Series. The park also boasted several unique new features, including a parking lot, constructed just off right field. And for the first time, a screen behind home plate was installed to protect the fans. The field at Fenway Park was laid out exactly the same as the one at The Huntington Avenue Grounds. The third base line runs south to north and the first base line runs west to east. The infield dirt and grass was brought over and transplanted from the infield at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. The Red Sox bullpen was located along the right field foul line. The visiting team’s bullpen was located in front of the left field grandstand. The playing field measured 320 feet down both the right field and left field lines. When needed, a fence was put on the field, running from right field to center field, behind which, fans could stand.

Fenway Park's left field wall would later become its most notable feature The main purpose of the 25 foot high wall was to keep people in the apartments on the other side of Lansdowne Street from getting to see the game for free from their roofs. There were two scoreboards on the wall. There was a manual scoreboard, showing the score inning by inning, and a lineup board posted just below it. Well to its right was the first of its kind, electric scoreboard. Lights for balls, strikes, and outs were lit up under the name of the batter. A large clock also sat atop the wall. Both scoreboards were surrounded by numerous billboards, advertising everything from Arrow Collars, and Stetson Hats, to Drakes Cakes and Mumm’s Rye Whiskey. Billboards were on all the fences that surrounded the field, as well as the walls above the bleachers. The first home run hit over the wall took place on April 26, 1912 by Hugh Bradley, but considering it was the “Dead Ball Era”, that feat was considered a fluke, and not likely to happen too often.

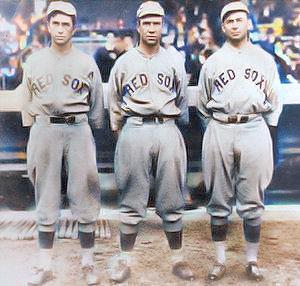

At the base of the left field wall was an earthwork incline, upon which a small set of bleachers was erected for the overflow crowds during World Series games. The incline’s real purpose was to support the left field wall, because Lansdowne Street was about 10 feet higher than the playing field. Boston's "Golden Outfield" of Harry Hooper, Tris Speaker, and Duffy Lewis were considered one of the best in baseball. Without the bleacher seats, the incline became an obstacle for all visiting outfielders, but was dubbed "Duffy's Cliff" because of Duffy Lewis' remarkable ability to be able to master the slope. "At the crack of the bat you'd turn and run up it. Then you had to pick up the ball and decide whether to jump, go right or left, or rush down again. It took plenty of practice. They made a mountain goat out of me." — Duffy Lewis

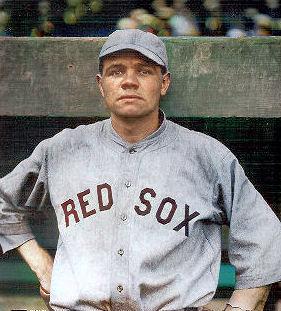

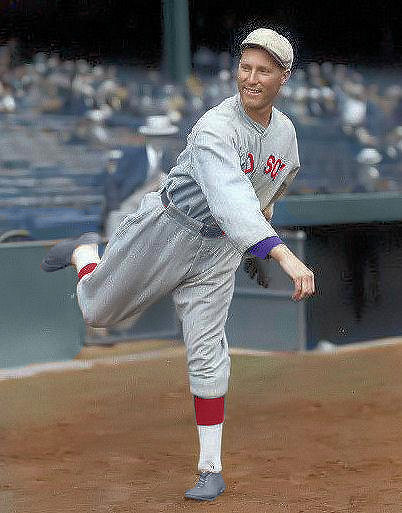

Center field was considered so deep at 468 feet, and 550 to the wall behind the flagpole, that it was of no consequence to a game. The last three years at the Huntington Avenue Grounds, the Red Sox averaged 33 home runs per year at home. At Fenway Park, they averaged only 21 homers per year over the first three years. Babe Ruth played for the Red Sox at Fenway Park for six years. In 1919, when he hit 29 home runs, only nine were at Fenway Park. In 1920, when he was bought by the Yankees, it was a gamble they were willing to take, because they played at the Polo Grounds, with its short right field fence. With this as his home field, Babe Ruth’s home run total at home, more than tripled that first year. The first official game at Fenway Park took place on April 20, 1912 after two rain outs, against the New York Highlanders (Yankees). The crowd of 22,000 was delighted as the Red Sox won 7-6 in eleven innings, thanks to a walk-off hit by Tris Speaker. The opening of Fenway Park also coincided with both the opening of the new stadiums for the Detroit Tigers, then called Navin Field, and of Redland Field, in Cincinnati. The opening of these new ballparks would have gotten front page publicity, had not one of the greatest catastrophes of all time dominated the newspapers ... the sinking of the Titanic. A formal dedication ceremony was postponed until May 17, 1912. Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, a staunch member of the “Royal Rooters” threw out the ceremonial first pitch. That year, the Red Sox went on to win the World Series with an unprecedented 105-47 season record. The season was highlighted by a long anticipated pitching duel took place between the two best pitchers in baseball, Walter Johnson (35-12) of the Senators, and Joe Wood (34-5) on September 6, 1912. Fenway Park had its largest attendance. The crowd was so big that, that day was the one and only time thousands of fans were allowed to sit or stand on the field, in foul territory behind ropes, during a game.

The Red Sox continued to dominate baseball from 1912 thru 1918. Fenway Park was the site of four of the five World Series’ played from 1914 through 1918. Since it was much bigger than the South End Grounds, Fenway was used as home for the “Miracle Braves” in the 1914 World Series. The Red Sox and Braves both called Fenway Park home for most of 1915 until the Braves moved into their new ballpark, Braves Field, in August. On September 9, 1918 the Star Spangled Banner was played before a game for the first time, as the “Yankee Division” from Massachusetts left to do battle in France.

Joseph Lannin was offered and purchased a 50% share in the Red Sox from James McAleer in 1913. James McAleer's tenure as part-owner of the Red Sox came to a swift end. On July 15, 1913, McAleer became involved in a dispute with the AL president, Ban Johnson, when McAleer forced the resignation of Red Sox manager Jake Stahl, one of Johnson's closest friends. Joe Lannin became complete owner, buying out the Taylors, McAleer and the partners in 1914.

In 1917, Lannin sold the team to broadway producer Harry Frazee. Frazee wanted to expand his entertainment holdings and was looking to get a foothold in sports. Frazee was a New Yorker and made his fortune as a theater producer on Broadway. A baseball fan, he initially attempted to buy the New York Giants. Frazee's purchase of the Red Sox was heavily leveraged because much of his money was tied-up in various Broadway theatrical productions. In November of 1916, along with his theater associate Hugh Ward, he purchased the Boston Red Sox from Joseph Lannin for $1,000,000. The Red Sox were coming off a World Series victory and were probably the best team in baseball, stocked full of young stars and a very valuable asset for Frazee to have in his portfolio. Lannin was highly-indebted and decided to sell high on his property, paying off his debts through the transaction. However, it was Frazee who in turn assumed a lot of debt, as he borrowed a large share of the cash amount paid to Lannin and quickly became tied down by the large amounts of interest due on the loans. He therefore found it difficult to honor promissory notes written to Lannin as part of the purchase agreement. When they came due Lannin threatened to sue to obtain the money due him in 1920, it forced Frazee to turn to his friend, Yankee owner, Jacob Ruppert for help. Ruppert took out a mortgage on Fenway Park for $300,000 and offered to give Frazee the cash he needed to pay Lannin. But it wasn’t enough. Frazee still needed money to run the operation.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 1,

The Yankee dynasty had now begun at the expense of the Red Sox. During the first three Yankee championship years, two hundred games were won by ex-Red Sox pitchers. The “Roaring Twenties” saw the construction of Yankee Stadium, the birth of “Murderer’s Row”, and the Babe become the toast of New York, along with his buddy, boxing legend Jack Dempsey. In Boston, the 1920s Red Sox become the Dead Sox. Bob Quinn proved not to be a good judge of baseball talent. He tried to rebuild the club and paid high prices for players who didn’t have much talent, or were over the hill. On the field, between 1921 and 1933, only two pitchers won twenty games. Red Ruffing lost 47 games himself for the Red Sox in 1928-29. The Red Sox dynasty spiraled into a second division team, finishing in last place from 1925 to 1930. In 1930, Quinn shipped Red Ruffing to the Yankees for Cedric Durst. Durst hit .240 and retired. Ruffing retired with a plaque in Cooperstown. As attendance dropped, so did revenues. Bob Quinn was in serious trouble. He had no money for players and without good talent he had little interest from the fans. Between 1924 and 1926, the attendance at Fenway Park only averaged 3000 per game. If not for Babe Ruth and the Yankees coming to town, the yearly attendance would not have reached 100,000. As a result, he ballpark fell into disrepair, with the minimum of maintenance.

The low point for Fenway Park came on May 8, 1926. During the game, several small fires erupted under the wooden left field grandstand. Although the fire was extinguished by the fans, at the time, the burnt trash was never cleaned up. Smoldering embers re-ignited during the evening and a full fledged blaze erupted. By the time the firemen arrived, the wooden left field stands were up in flames as well as the central grandstand roof. The blaze was contained and put out, but not before $25,000 worth of damage was done. Insurance covered the cost and a new roof was built over the central grandstand, but Quinn took the remainder of the insurance money to make payroll. The burnt remains of the left field stands (today’s sections 29 thru 33) were simply hauled away and the area remained empty. It did, however, give Fenway Park an interesting new feature. This great expanse of now empty foul territory from the wall behind the central grandstand out to the left field wall remained “in play”. Base runners could not see if foul balls were caught when fielders ran out of their sight.

With the 1929 stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, the fortunes of Bob Quinn and the Red Sox went from bad to worse. The once proud Red Sox had been borrowed and bargained into near oblivion. Quinn needed to sell the club, just to finally get out of debt. Jacob Ruppert still held a second mortgage on Fenway Park, and Quinn owed concessionaire, Harry Stevens $150,000. The once flagship franchise of the American League had hit rock bottom. It was hard to imagine why anyone, with the economic conditions as they were, would want to buy the Red Sox. In 1933, he sold the team along with shabby Fenway Park, for 1.2 million, a bargain for the real estate alone, even at Depression era prices. The Fenway Park real estate alone was worth more than that. The buyer was thirty year old, Tom Yawkey. Yawkey was a quiet man with many acquaintances but few friends. He idolized baseball people but felt insecure in their company. Yawkey would live vicariously through his new ball club, reflecting his character. He was the first of a new breed of owner, a man child playing with millions of dollars. He needed a baseball man to do the work, because he knew nothing about running a baseball organization. So he lured his friend Eddie Collins away from the Philadelphia Athletics to run his team. Yawkey’s checkbook came out and he announced his intention to the other money-strapped owners that he was going to restock his Red Sox and price was no object. In only five days, while Americans were begging in the streets for food, Yawkey spent a quarter of a million dollars on ballplayers. In doing so, he had raised the level of what baseball players were worth. Like Yankee owner, Jacob Ruppert, who had taken advantage of the misfortune of Harry Frazee, to gut the Red Sox over a decade before, Tom Yawkey was now in a position to do the same thing to all of baseball.

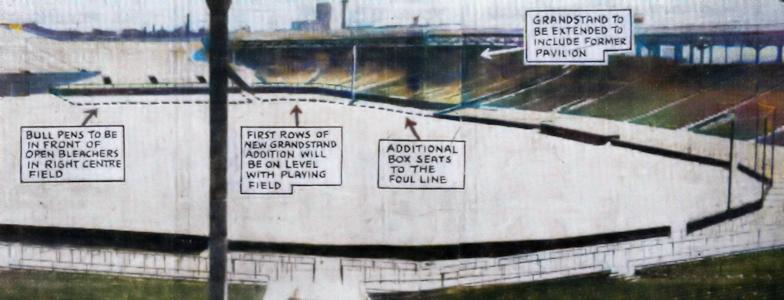

The next thing Tom Yawkey set out to accomplish was rebuild the neglected and derelict ball yard. In the 1934 off-season Coleman Brothers Construction was given the contract and started the renovation, with the goal being completion for the opening day of the 1934 baseball season. Building actually commenced during the Boston Redskins’ football season, so the wooden bleachers in center field and right field had to remain untouched until the Redskins season ended. The rebuilding of Fenway Park was very significant to the people of Boston during the Great Depression. Yawkey employed close to 750 skilled union workers. Because of the vast amounts of concrete, steel, bricks, and lumber needed, the project was a major boon to the economy of the area. During the winter, the unexpected happened. With the overhaul well under way, on January 5th a fire broke out, went to five alarms and in the process, destroyed the not only center field bleachers and surrounding area. Six weeks later, on February 19th, a second fire had to be contained. The causes of the fires were speculative, but all in all, the fires did $250,000 worth of damage. Despite the setback, rebuilding progressed on schedule, with workers putting in double shifts, and 300 additional laborers hired. As a matter of fact, because it was winter, a wooden house was erected in left field where the workers could take breaks and sleep. The wooden grandstands and bleachers were all replaced with concrete and steel, and a roof covered all but the outfield bleachers. All in all 15,000 additional seats were added in the process. On the field, home plate was moved toward the center of the park, greatly reducing the size of the outfield. The distance to center field went from 468 feet to 420 feet, and the distance to right field went from 358 feet to 344 feet. The Red Sox bullpen was located in front of the right field foul pole, and the visiting team’s bullpen remained in front of the left field grandstand. Both bullpens remained in these positions until the next big renovation in 1940.

The old left field wall was torn down and replaced with one that is connected to the left field stands and center field bleachers. Duffy’s cliff was no longer needed to support the wall and was flattened to field level, so temporary bleacher seats could be erected during football season. The new 37 ft wall was made of wooden railroad ties in the upper section sitting on an 18 ft high lower concrete foundation. It was covered in tin and finally painted green as was the rest of the ballpark. When a ball would hit the railroad ties it ricocheted toward the infield, but when it found tin with nothing behind it, the ball deadened and dropped straight down. Carl Yastrzemski would later master the structure of the wall and knew exactly how to play every little nuance.

Later, in 1936, a 23 ft tall screen was installed above the wall to protect the houses that lined the other side of Lansdowne Street, and a permanent ladder was attached to the wall to access the screen for retrieving baseballs. To this day, the ladder remains in play during games, and has created many interesting situations over the years. As with the old wall, advertising was still prominent. During the 1930s and 1940s, the billboards were as much a part of Fenway Park as the wall itself. The Calvert Brewery’s owl resided there, telling customers to “Be wise”. Gem Razor Blades warned you to “Avoid the 5 o’clock Shadow”, while Lifebuoy Soap boasted “The Red Sox Use It”. High above the wall the Cities Service sign has looked down from Kenmore Square, since 1940. The sign became the familiar electric one in 1965, as Cities Service changed its name to Citgo. In 1979, the sign was shut off, but the outcry was so overwhelming, that the idea of landmark status was actually considered. As a result in 1983, it was completely refurbished, and is now considered a piece of urban art. A t the base of the wall was a new scoreboard. Electrically, there were green lights for the count of balls, red lights for strikes, and outs, and there was a green light for a hit and red for an error. Finally, the uniform number of the player, who was at bat, was also displayed with lights. The score of game was always posted manually. The scoreboard also displayed the scores of other American League games, inning by inning, but showed only the total score of the National League games being played.

The final touch might go unnoticed, but in 1947, the initials of Tom Yawkey and Jean Yawkey were written in morse code, running vertically on two of the white dividing lines (TAY-JRY). On the top of the left field wall sat a bank of speakers for the public address system. Above the bleachers in right field, was a 20 ft fence, installed for protection above the last row, along with an ad for Gruen Watches. Initially a clock sat atop the center field bleachers. Eventually it was moved above the right field bleachers.

The renovated ball park opened on

April 17, 1934. The Sox lost to the

Senators, 6 to 5, however

Yawkey's

investment would soon pay off as he

invested in a quality ball park to

soon be filled with quality ball

players. Future Hall-of-Famers left

their teams to take up residence at

Fenway Park.

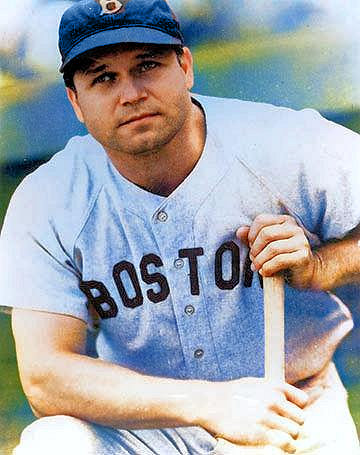

Players such as 20 game winner Lefty Grove, followed by catcher Rick Ferrell, speedy Billy Werber and George Pipgras in 1934 became Red Sox. All Star shortstop Joe Cronin came to Boston in 1935, and was followed in 1936 by right handed slugger, Jimmie Foxx. Two years later Foxx hit a club record, 50 home runs. Tom Yawkey not only signed these superstars, but was the first owner to pay high salaries. Yawkey also put money into his minor league farm system, a system that would eventually produce Bobby Doerr in 1937 and in 1939, Ted Williams.

As Tom Yawkey continued to build in the 1930s, attendance at Fenway Park increased. 350,000 more fans came the gates during the first year of the new ballpark, than did the year before. On September 22, 1935, a doubleheader with the Yankees drew 47,627 fans. Interestingly enough, because of today’s more stringent fire laws, this will forever remain the attendance record, unless Fenway Park drastically changes.

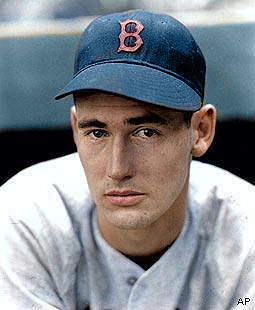

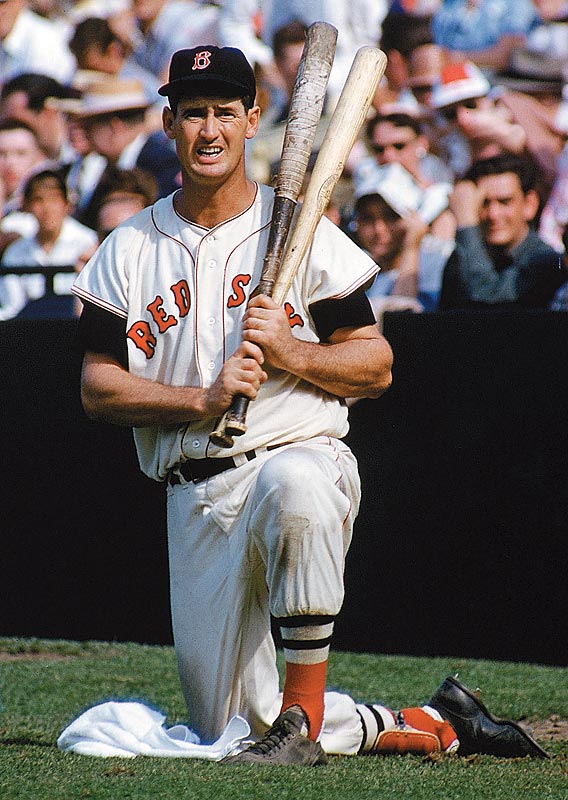

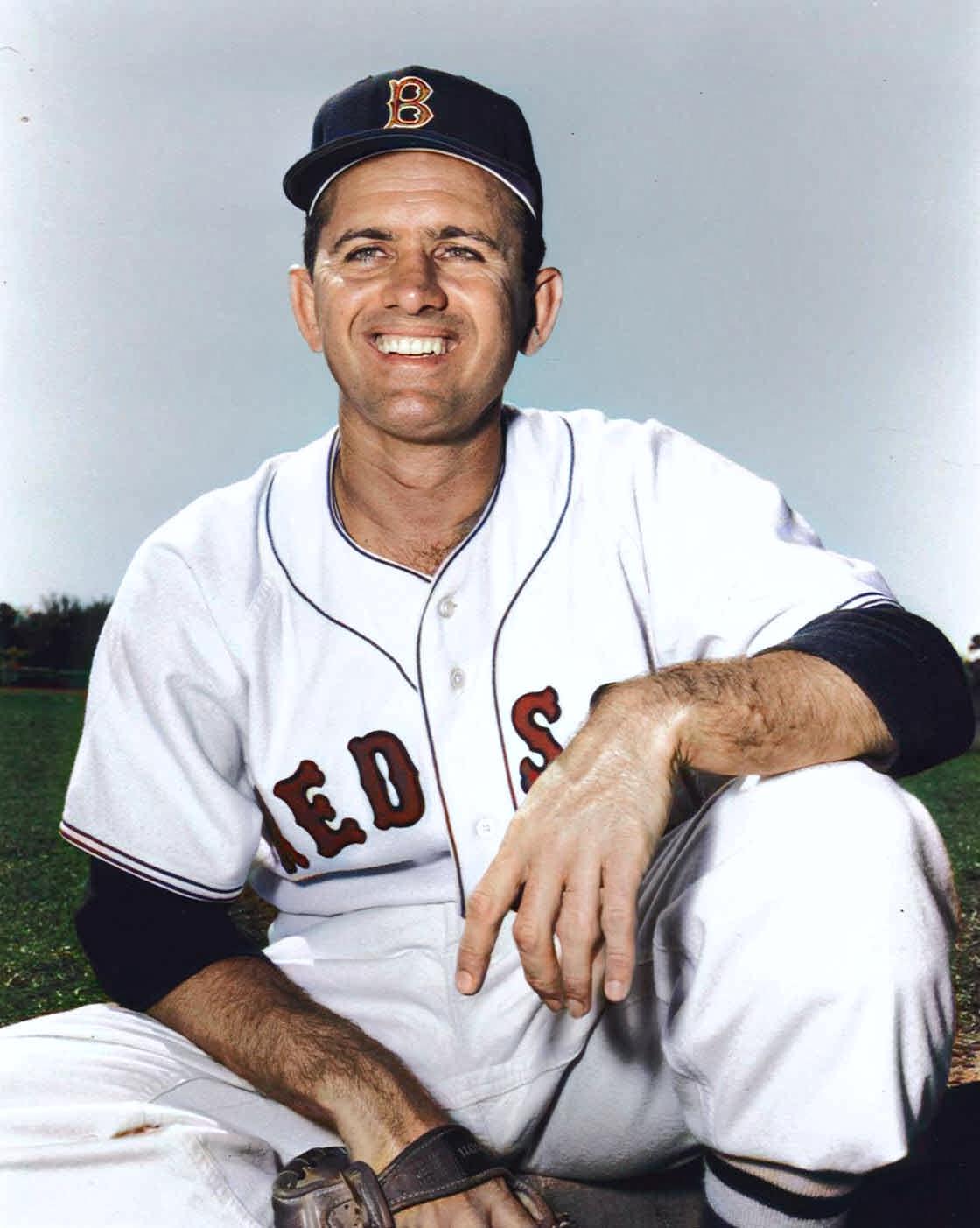

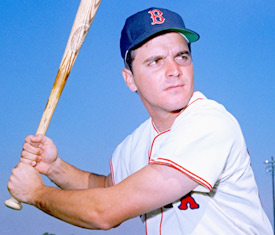

Ted Williams

made such an impression, that in

1940,

Tom Yawkey undertook yet

another renovation to accommodate his

young left-handed power hitter. The bullpens were relocated to their

present location, in front of the

right field bleachers.

Protected by a 4 ft wall in front,

the right field fence was now 23 feet

closer. The bullpens were

dubbed by the sportswriters as

“Williamsburg”. The corner in

right field was also rounded off.

Known as “The Belly”, new seats were

installed where the old bullpen had

been located, bringing in the right

field foul pole, some 30 ft. Now, pop flies down the right field

line had a good chance of sneaking by

the foul pole, into the grandstand

for home runs. The foul pole

was later nicknamed “Pesky's Pole” by

pitcher

Mel Parnell in the 1940s, because

of

Johnny Pesky’s uncanny ability to

hit it, resulting in home runs.

Since the visitor’s bullpen along

third base, was no longer used, the

front of left field grandstand was

extended forward toward the field

with new seats added.

Fenway Park was also home to the Boston Redskins who had moved over from Braves Field in 1933. In their last season in Boston, the 1936 Redskins won their final three games, outscoring their opponents 74-6, and captured the Eastern Division Championship with a 7-5 record. Because of extremely poor attendance, highlighted by only 4813 fans coming out to Fenway to see the Redskins trounce the Pittsburgh Pirates, 30-0, Redskins owner, George Preston Marshall, was so angry, that he elected to give up home field advantage and played the NFL Championship game, against the Green Bay Packers at the Polo Grounds in New York. The Redskins never played in Boston again, moving to Washington for the 1937 season.

The National Football League came back to Fenway Park in 1944. The owner of new franchise, Ted Collins, had named the club, the New York “Football” Yankees and wanted the franchise to play at Yankee Stadium, but leasing arrangements and a block by the existing New York “Football” Giants, caused him to shift the team to Boston. Here, Collins shortened to the team name to the Yanks. How ironic, that a Boston based team was nicknamed after their New York rival in baseball. Until 1948 the Boston Yanks played their games at Fenway Park. That year, however, they merged with the Brooklyn “Football” Dodgers and split their home games in both Fenway Park and Ebbets Field. Then, in 1949, Collins had the opportunity to move the team back to New York and did so. The franchise name was changed to the Bulldogs, but eventually folded in 1951. What was left of the franchise found its way to Baltimore in 1952, becoming the Colts. The Yanks’ schedule was painted on the left field wall, to the left of the scoreboard, while the Red Sox next game, was posted to the right of the scoreboard. The tradition of noting the Red Sox next game continued until 1960.

The year, 1941 will go down as a year in Red Sox history, right along side 1912 and 2004. In July, Ted Williams won the All Star Game in Detroit, with a walk-off home run. As the summer progressed, the country became transfixed with Joe DiMaggio hitting in 56 straight games. Quietly, Ted Williams’ batting average was .402 in August. In September it was .413 and going the final day of the season, he was batting exactly .400 Williams could have sat out, but being so competitive, he wouldn’t hear of it and was determined to play in both games of a doubleheader on the last day. He went six-for-eight and finished the season at .406 A month later Nazi tanks headed toward Moscow and in December the Japanese stared down at Pearl Harbor. In 1942, Ted Williams won the triple crown and then joined the Navy.

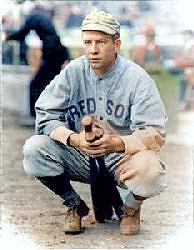

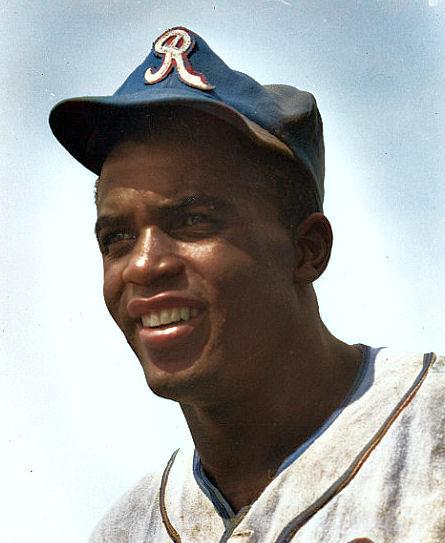

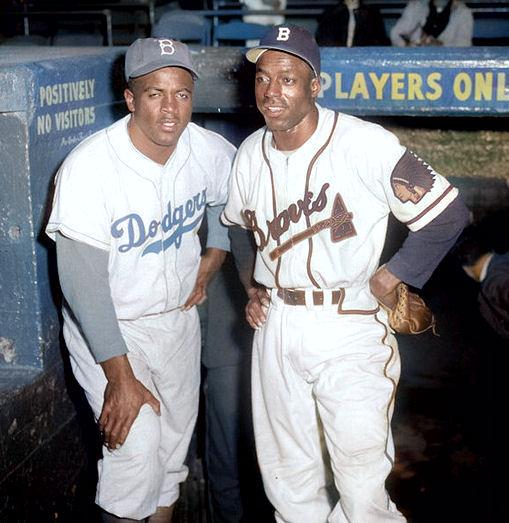

Black baseball in Boston started in the 1870s, when the City League formed teams of men. Though the Boston Royal Giants were never among the most nationally popular black semi-pro teams, Boston was a hotbed of black baseball in the 1930s and 1940s. The Royal Giants sometimes played in the famed Boston Park League. Venues that hosted the Giants were often small public parks such as Medford's Playstead Park and Boston's Lincoln Park, but Braves Field rented to Negro League owners as early as 1938, and Fenway Park was used for heavily-promoted games after 1942. During the war, there obviously was a need for replacements to keep baseball alive, while soldiers like Ted Williams went off to serve. It became very apparent that the players in the Negro Leagues would eventually be given their long overdue chance. The Red Sox, like most major league clubs regularly held tryouts hoping to pick up a player or two from among those either too young to serve in the military or otherwise unqualified. The Red Sox had the opportunity to add some talent to the roster in early April of 1945. On the morning on Monday, April 16th, Boston city Councilman Isadore Muchnick and sportswriter Wendell Smith and three African-American baseball players from the Negro leagues arrived at Boston’s Fenway Park. One month earlier the Red Sox reluctantly agreed to hold a tryout for African American ballplayers. Shortstop Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, second baseman Marvin Williams of the Philadelphia Stars and outfielder Sam Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes came to Boston for a tryout at Fenway Park in front of manager, Joe Cronin. At 10:30 a.m. Williams, Jethroe and Robinson, met by Sox scout Larry Woodall and aging coach and former player Hugh Duffy, took the field. A small group of amateur and semi-pro players were already working out, for World War II had depleted the Red Sox organization. Jackie Robinson went to shortstop. Marvin Williams played second base. Sam Jethroe jogged to the outfield. Wendell Smith and Isadore Muchnick sat in the stands, as did Red Sox manager Joe Cronin. If Collins or any other Red Sox official watched, they did so out of sight, either from the shadows beneath the grandstand roof or from the press box. As the other players at the workout scattered, Woodall and Duffy put the three players through the paces. They first took fielding practice, taking grounders, fly balls, and throwing. Then the players took batting practice. All three men reportedly demonstrated some ability, but according to most accounts Jackie Robinson performed best. After an hour and half or so, the workout ended. The three men retreated to the locker room to change, and then “all three were given the customary forms in which to enter their athletic history and background,” standard procedure when scouting a prospect. The Red Sox never contacted the players again. Neither did they scout or hold tryouts for other African American players until long after the color line was broken. For a team that was the last to field an African American, Pumpsie Green in 1959, it’s of interest that the Red Sox in 1933, 1934, and 1935 had Native American Roy Johnson playing left field and Mexican Mel Almada playing center.

The years after the war were extraordinary for baseball in many ways. Baseball symbolized a return to normalcy for Americans. It wasn’t just the numbers, there was a special intensity to the crowds. Baseball was rooted in the past, but after the war, it predominated the culture. The sons of the immigrants, who migrated to the United States in the early part of the century, now became the stars of post war baseball.

In 1947, with the coming of Jackie

Robinson and the other players of the

Negro Leagues, baseball truly became

America’s pastime, where anybody

could dream of becoming a big

leaguer. The year after the

war, attendance at baseball parks

literally doubled. Baseball broke its

all time attendance record in 1946 by

80 percent. Attendance at

Fenway Park tripled.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 2,

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 3,

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 4,

The post war Red Sox put out some of the best teams since the championship years of the 1910s. Each year, they came so far but ultimately couldn’t close the deal. It would be close to twenty years before they came close to getting another chance.

In 1946, the next set of major changes came to Fenway. Yawkey erected a small area of seating on top of the grandstand roof down the first base and third bases sides, known as the “Skyview” seats. A year later, the Red Sox became the fourteenth of the sixteen major league teams to put up lights and adopt night baseball. The Red Sox defeated the White Sox, 5-3 in the first night game on June 13, 1947. That year the billboards disappeared from the left field wall under a coat of green paint because Ted Williams claimed they were a distraction during night games with the glare of the lights. It was then that the legend of the "Green Monster" was born although it would be many years before the wall was referred to by that name.

Led by the advent of television, the

technological revolution was about to

take hold in the United States.

In 1947, the World Series was

telecast to a few eastern cities, but

at the moment, it was radio that put

the fans in daily contact with their

team. It was radio that made

the games and the players vastly more

important than they were and raised

players to heroic stature.

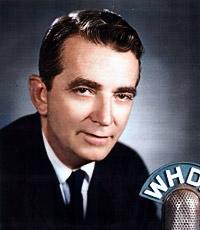

On May 12, 1948, the first televised baseball game came to Fenway Park. Since 1925, radio broadcasts of Red Sox and Braves games had been handled by Fred Hoey. For TV, the voice of both the Red Sox and the Braves was Jim Britt with color man, Leo Egan. In 1951 Curt Gowdy became the Red Sox broadcaster. It was a job he held until 1965. At Fenway, a small booth for the broadcasters was erected above the backstop screen in 1949. The only access to the TV booth was by climbing down a ladder, from the “Skyview” seats up above. The broadcasters moved upstairs in the 1990 press box renovation and the small booth remained as a base for television cameras. During the 2005 renovation, it was finally dismantled, because a small remote controlled TV camera was able to be hid just above the backstop screen.

The beginning of the Curt Gowdy era of the 1950s saw the Red Sox become the “Ted Sox”. Big salaries were paid to players who didn’t deserve it. Front office executives were a part of Tom Yawkey’s good old boy network. The mainstays of the championship teams, Bobby Doerr, Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio all retired. During this decade, the team went from bad to worse. The results on the field revolved around one man only ... Ted Williams. After coming back a hero in Korean War, Williams attained mythic status. Big name players, like Mickey Mantle and Al Kaline became awe struck, just watching him take batting practice. Williams was very free with advice and quite often found himself giving free clinics to the opposing players who had gathered around to listen. In 1952, the next change came to Fenway Park, as the visitor’s clubhouse was moved over to the third base side and connected to the dugout.

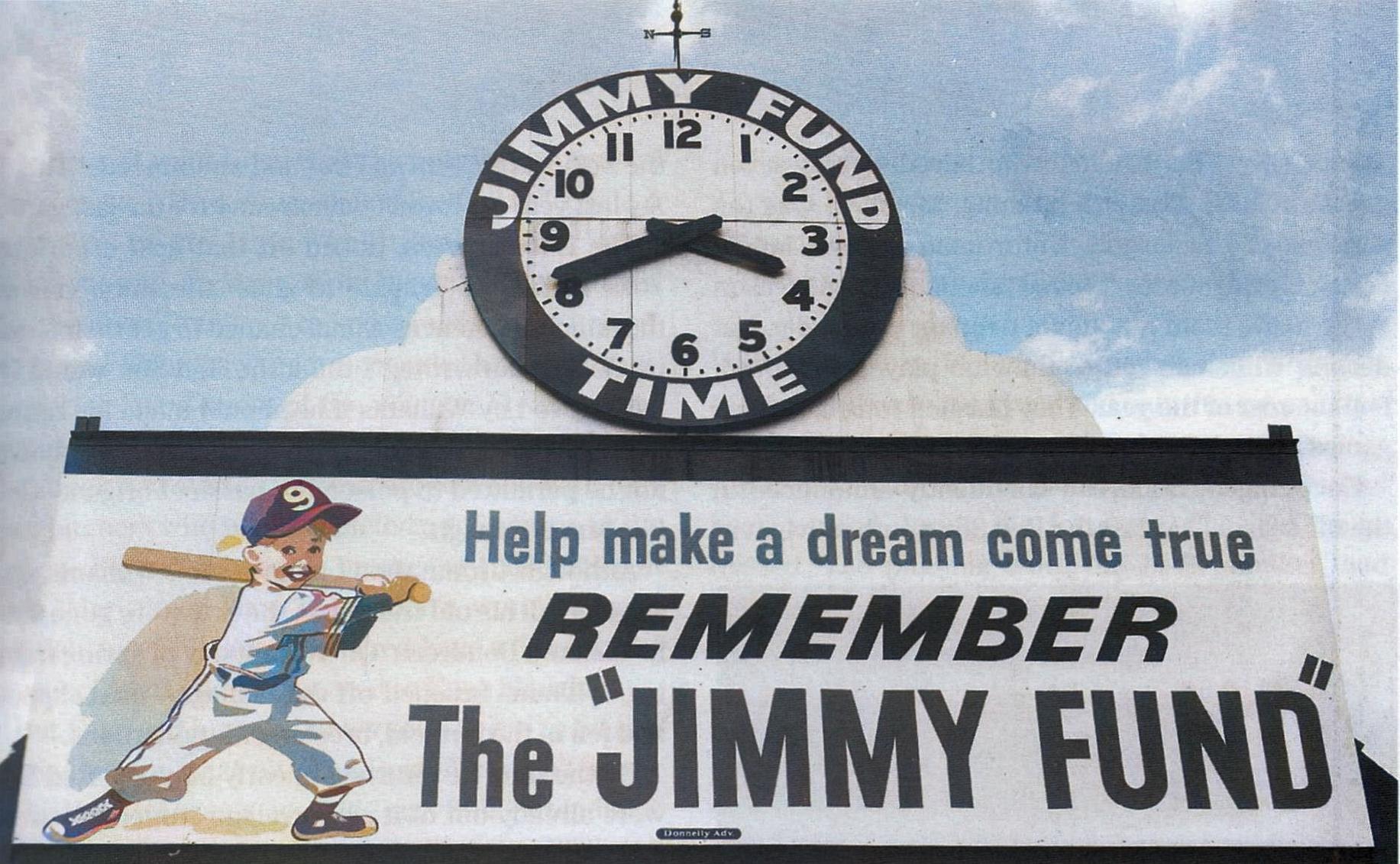

In 1953, feeling they were no longer able to compete with the Red Sox for the fan base, the Boston Braves shocked the baseball world and moved to Milwaukee. Lou Perini, the owner of the Braves asked Tom Yawkey to please adopt the charity he had started, to help battle cancer in kids ... it is called the Jimmy Fund. For many years the Braves came back to Boston to play in a Jimmy Fund charity game with the Red Sox, an event that continued into the 1960s. A sign that reminding fans not to forget this charity sat on the right field grandstand roof for over fifty years. This was the only advertising allowed to be displayed at Fenway Park until the 1990s. In the years following the departure of the Braves, attendance at Fenway Park didn’t rise appreciably. The irony of the situation is that while the Red Sox slipped into a malaise in the 1950s, the Braves grew into World Series winners in 1957 and 1958. Had the Braves stayed in Boston, maybe the Red Sox would have thought about leaving town instead.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 5,

Mel Parnell was the only 20 game winner for the Red Sox in the 1950s, and the farm system produced only mediocre players. The fans just stopped showing up to see a team that never finished less than 11 games out of first place at the end of the season. But Tom Yawkey blamed the slipping attendance to a lack of parking. So, in 1958, he unveiled a plan to tear down the left field wall, build a left field grandstand, and add on-site parking. Yawkey could afford to buy the land and do the project on his own, but thought public money should help to finance the project, as was being done in other parts of the city. He met with unsympathetic ears on Beacon Hill, and soon abandoned his idea. By the end of the 1950s, Ted Williams lost interest in a team going nowhere. He had always been very active in the Jimmy Fund, but fishing became more and more important to him than baseball. On the field he was always the story. In 1957 he made another run at batting .400 finishing the season with a .388 batting average. In 1960, Ted Williams was named the Player of the Decade, made another run at a batting title, and retired by hitting a home run in his last at bat, on the last day of the season. Without Ted Williams, the team further slipped down in the standings during the early 1960s. And without Ted, Tom Yawkey’s indifference to his club intensified, as every year passed. Attendance sagged to around 750,000.

In 1962, each league added two expansion teams. The left field scoreboard had to be redesigned to accommodate the change. Eliminated were the inning-by-inning scores of the American League teams, and the format used for reporting National League scores of showing the score and inning only, was constructed for A.L. scores also. The green and red lights were moved underneath the Red Sox complete game score. Finally, the umpires were also listed for the one and only time, at the end of the American League scores. Only the mounting of the numbers are the responsibility of the crew inside the scoreboard. The electric part of the scoreboard is controlled upstairs. In addition, a new electric lineup board was installed to the right of the scoreboard. Finally, in right field, the clock above the bleachers was replaced with an auxiliary scoreboard.

In 1963 the Red Sox added more night games and that fall, agreed to lease the park to the fledgling Boston Patriots. That first year, the Boston Patriots finished tied for the Eastern Division title with the Buffalo Bills. The 1963 Patriots made it to the A.F.L. Championship game by beating the Bills 26-8 in a playoff, only to lose to the San Diego Chargers, 51-10. Again, in 1964, led by Gino Cappelletti, the Patriots went 10-2-1 only to lose their chance at a second consecutive A.F.L. Championship game by losing to the Bills, 24-14 on the last day of the season. The Patriots started a downward spiral after this. Their only real bright spots during the rest of their stay at Fenway Park, were Hall-of-Famer Nick Buoniconti and running back Jim Nance. In 1966, Nance rushed for 1,458 yards, establishing an American Football League record.

Patriot’s owner, Billy Sullivan wanted his own stadium. He pushed to chair a commission for exploring the possibility to get the city to build a new 60,000 seat domed stadium, with a retractable roof in the South Station section of Boston. Tom Yawkey signed on to the idea, in hopes that a new stadium might fall on progressive ears that would listen, considering within the city’s aggressive plans for redevelopment in the early 1960s. But the city, as before, had no desire to fund a private stadium and again, the plan didn’t see the light of day. The Patriots played at Fenway Park until 1968, and eventually moved to their own stadium in Foxboro in 1971. For Patriots games at Fenway Park, a set of temporary bleachers was erected in front of the left field wall, and the markings on the auxiliary scoreboard above the right field bleachers, were altered to display football information. A temporary football scoreboard was placed on the roof next to the third base “Skyview” seats, overlooking the end zone.

In 1961, there were only a few bright spots in the organization. One was an intelligent executive, who was convinced that success started with a strong minor league system. As Dick O’Connell started to rebuild the club from the bottom up, minor changes were made to with the hopes of building attendance. The other was Carl Yastrzemski, who had the unenviable task of replacing Ted Williams in left field.

With

Yastrzemski, local star,

Tony Conigliaro, and a slick

fielding slugging first baseman named

George Scott, the Red Sox had

potent bats in the mid 1960s, but

still had poor pitching. The

only bright prospect was a pitcher

named

Jim Lonborg. Year after

year, the team sat closer to last

place than to first place in the

American League standings. The Red

Sox hit bottom in 1965, losing 100

games ... something which had not

been done since 1932.

At Fenway Park, the corner of the center field bleachers was regularly a problem for a batter’s vision during day games. When the park was full, fans wearing white posed a problem for batters, trying to pick up the ball, coming out of the pitcher’s hand. In 1965, Tony Conigliaro asked the bleacher fans, who sat here not to wear white. That triangle of seats was dubbed “Conig’s Corner” in 1965, and eventually was closed off to fans and covered with black netting, only to be accessed when all other areas of the park were full. When regular television broadcasts of baseball games gained popularity in the 1960s, this area became used as a base for the center field television cameras.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 6,

Determined to make things change, Dick O’Connell hired his top minor league manager, Dick Williams. Williams was ano nonsense personality, and in 1967 decided to go with his rookies and second year players, whom he knew from the minor leagues, rather than the overpriced veterans. 1967 started with a near no-hitter by rookie Billy Rohr and ended with an American League pennant. Along the way Carl Yastrzemski, hit clutch hit after clutch hit and won the Triple Crown. When the dust settled, the Red Sox had achieved what was dubbed “The Impossible Dream”. As in 1946, it was the St. Louis Cardinals who ended up putting an end to the dream of another World Series Championship.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 7,

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 8,

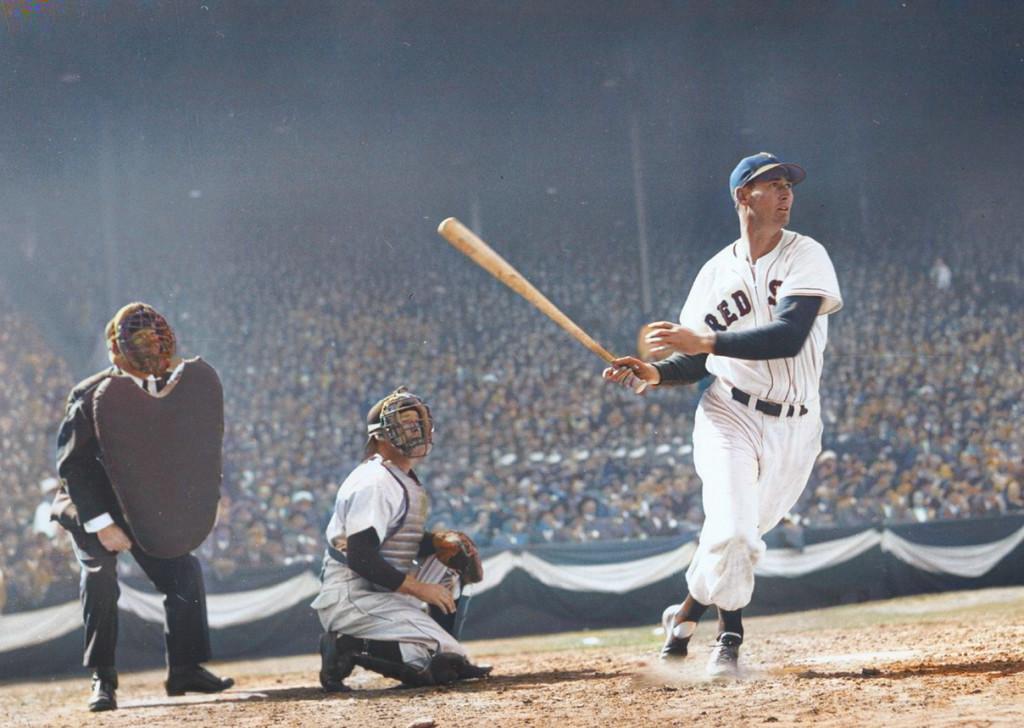

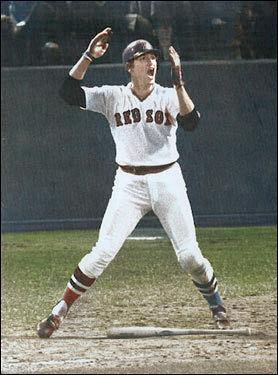

The Red Sox had continued to build in the early 1970s, while playing competitive on the field. Luis Tiant was acquired from the Indians and the farm system started to blossom and produce. Bill Lee, Carlton Fisk, Dwight Evans, Jim Rice and Fred Lynn moved up thru the system to take their place on the big club. The payoff came in 1975, when Fred Lynn made such an impression that he won both “Rookie of the Year” and A.L. MVP honors. The Red Sox took their second pennant in less than ten years. In what some people think as the best World Series ever played, the Red Sox, highlighted by Carlton Fisk’s 12th inning walk off home run in Game #6, yet again fell short to the Cincinnati Reds in the finale.

In 1976, Fenway underwent a major facelift. The left field wall was rebuilt out of a hard plastic, giving balls hit off the wall a truer bounce. Six foot padding was put up on all the walls, because of the near concussion Fred Lynn experienced, after running into the concrete part of the left field wall, in the 1975 World Series. Fenway’s first message board was constructed high above the center field bleachers in 1976. The scoreboard on the left field wall underwent another facelift. The National League side of the scoreboard was eliminated, as well as the electric lineup board.

1976 saw the beginning of free agency in baseball. Tom Yawkey deeply resented it. He paid enormous sums and expected loyalty from his players in return. He also was a very sick man and the new order in baseball wore on him. He passed away on July 9th and ownership of the club stayed in a trust, administered by his wife, Jean Yawkey, Buddy LeRoux and Haywood Sullivan. Tom Yawkey would always be remembered, as a philanthropist, a surrogate father to his players, and as the owner, who owned a team longer than anyone, yet never won a World Series. He did more to preserve Fenway Park and make it the shrine it has become. First, he saved it by rebuilding it. Then, even after admitting that it was a detriment to his own personal financial ambitions, he continued to preserve it, even though he had the financial wealth to build a modern facility as Walter O’Malley did in Los Angeles for the Dodgers. At the time of his death, the Red Sox and Fenway Park were worth an estimated $20 million, a far cry from the $1.2 million he paid Bob Quinn for the club in 1933. As a tribute to him, the street running in front of Fenway Park, Jersey Street, was renamed “Yawkey Way” in 1977.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 9,

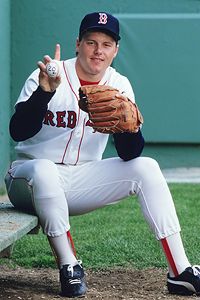

In 1982, luxury boxes were erected on the rooftop and Wade Boggs was inserted at third base. In 1984 roof boxes were added, as was Roger Clemens. Their greatest pitcher since Cy Young led them to another American League Pennant in 1986 and in the process struck out a record twenty Seattle Mariners one night in April.

The Curse of the Bambino, Part 10,

In 1988-1989 stadium seating was built behind home plate, above the grandstand where the press box had been located. It was named “The 600 Club”, but when Ted Williams died in 2002, the name was changed to “The .406 Club” in his honor. A new, press box was built atop “The .406 Club”. A side effect of the huge press box was that the wind currents changed and affected fly balls. In 1992, a metal awning was installed above the roof boxes.

Jean Yawkey passed away in 1992 and John Harrington took over the operations of the Yawkey Trust. On the field, the Red Sox signed mediocre free agents and paid them high salaries, resulting in disappointment. Finally realizing that the game plan wasn’t working, Dan Duquette was hired as general manager, and given the task of rebuilding the team efficiently and especially the minor league system. In 1995, led by Mo Vaughn, the Red Sox won a division title. In 1997, Roger Clemens left via free agency, but the Red Sox found Nomar Garciaparra. In 1998, they signed Pedro Martinez, traded for Jason Varitek, and made it back to the playoffs. In 1999, Pedro became only the third pitcher in Red Sox history to win a Cy Young award. For years, advertising was not allowed to be displayed in the park. That changed in 1997, when two giant “Coca-Cola” bottles were erected on the left field light tower. Since then billboards have been plastered in almost every piece of space all over the inside of the park.

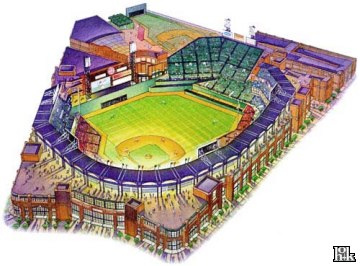

In the 1990s, new ballparks were

either being built or being planned.

After Camden Yards opened in

Baltimore (1992) Jacobs Field in

Cleveland (1994), and Coors Field in

Denver (1994), plans were being made

by most other cities to build their

own version of a ballpark that had

the feeling of a classic ballpark of

the past (like Fenway Park) but with

the modern conveniences a new park

would incorporate. With the

century coming to a close, the talk

was no different in Boston. For

all its charm, Fenway Park was the

oldest ball yard in baseball.

On May 15, 1999 the Red Sox and the

Yawkey Trust, under, John Harrington

unveiled plans for a new ballpark.

The proposed new park was to be built

on the other side of Jersey Street,

maintaining the same footprint of

Fenway Park, but incorporating all

the new amenities. In spite of

protests by local neighborhood groups

and preservationists, John Harrington

pushed to make the dream a reality.

The problem was, he didn’t own the

land and didn’t have the money to buy

it and then build the park. The

cost was $627 million. The Red

Sox wanted the city to provide some

$275 million. Again, as in the

past, the city was not about to

finance the venture. In 2000, a

relentless public relations push was

launched to get the deal done for the

new park. It wasn’t going to happen.

The end came on October 6th,

when Harrington threw in the towel

and announced that they had decided

to sell the Red Sox ... the Yawkey

connection had reached the end of the

road.

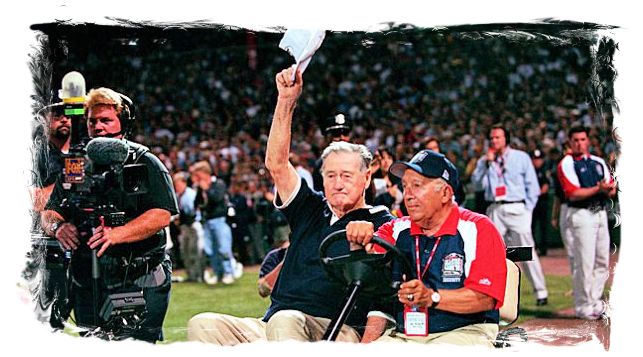

Fenway Park's greatest moment

occurred before the 1999 All Star Game.

Ted Williams returned to

Fenway and was correctly introduced as “the greatest hitter that ever

lived,’’ ... Teddy Ballgame, now 80, rode around the park on a golf cart

and after his victory lap,

In 2002, The Red Sox were purchased by a group headed by John Henry and Tom Werner. Immediately changes came to Fenway Park, as their commitment to preserve the historic ballpark was demonstrated. 149 roof box seats were added and 160 dugout seats in two additional rows of box seats pushed their way out toward the infield. One of the biggest and innovative changes in the history of the ballpark took place in 2003. The “Green Monster Seats” were added above the left field wall, and immediately became proclaimed the best seats ever constructed at Fenway Park. 2003, marked a return to billboard advertising on the left field wall. For the first time in over fifty years, two ads were allowed to be placed next to the scoreboard ... one for “Bob’s Stores” and the other for “W.B. Mason” office supplies. The scoreboard was expanded to include the American League east standings. Above the left-centerfield bleachers, an electronic “Pitcher’s Board” and “Batter’s Board” was erected to give additional information on the current pitcher and batter. Upstairs, the “.406 Club” was refurbished and the Red Sox opened the “Legends Suite” where fans could watch the game, with a former Red Sox star. Down below, the Red Sox received the gift of a batting tunnel, bat swing area and pitcher’s mound ... all behind the Red Sox dugout, located under the stands.

Outside, after a trial run in September 2002, the street concourse on Jersey Street opened. From “El Tiante’s” to “Remdawgs”, a large menu of food and other outdoor activities, such as the NESN pre-game show, were there for the fans before each game. Later in the season, during July, the large concourse under the right field bleachers opened, along with the ticket booths at Gates, B,C & D.

Over the years Fenway Park has hosted many concerts during the summer. In 1973 Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles first performed at Fenway. Starting up again in 2003, Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, Jimmy Buffett, Billy Joel, Neil Diamond, The Police, Jason Aldean, the Zac Brown Band, Tom Petty, Aerosmith, James Taylor, the Dave Mathews Band, and the Rolling Stones are among those who have performed to great summertime crowds. In 2004, high above the right field grandstand, the “Budweiser Pavilion” was erected on the roof, providing fans with café style seating for 192 people and space for 250 standing room patrons. Gone was the familiar “Jimmy Fund” sign, but replacing it outside the right field concourse, the Ted Williams “Jimmy Fund” statue was unveiled. Sidewalks were widened, as well as the addition of historic light fixtures and a new food court was opened in the third base concourse.

The Curse is Reversed,

The Sox proceeded to make the greatest comeback in the history of baseball. Not only did they rally to win that game, but won the next three games, to eliminate the Yankees and win the pennant. It was a series where Curt Schilling became legend by pitching with in innovative surgical procedure to the injured tendon of his ankle, just so he could pitch. The Sox then breezed by the St. Louis Cardinals to win their first World Series since 1918. Led by Josh Beckett, Manny Ramirez and David Ortiz, in 2007, the Red Sox marched their way to their second World Series Championship of the 21st Century with a four game sweep of the Colorado Rockies.

On the opening day of the 2005 season, the World Championship banner was unfurled over a playing field that had been updated with a state-of-the-art irrigation and drainage system, The left field wall that had again changed. A third ad for “CVS Pharmacy” was allowed in the left field corner. And in 2006 a billboard for “Granite City Electric” was added and “F.W. Webb” replaced the “Bob’s Stores” sign. The exterior of the park also received a facelift in 2005. The brick masonry of the building was restored to its early 1900s appearance, along with historic arched windows, light fixtures and awnings. 2006 saw major construction taking place on the upper decks. “The .401 Club” glass was removed, and renamed the “EMC Club”. In addition, a new food concourse was constructed behind the third base grandstand. A third level of seating was erected along the first and third base sides. These upper level seats are known as “The State Street Pavilion”. The total new number of seats gained from reconstruction, was 1300. For the players on the field, protective posts and screens were erected in front of both dugouts. The following year, a visitor’s batting cage was built and the “Jordan’s Third Base Deck and Concourse” was constructed.

In 2008, the giant Coke Bottles were removed from the Green Monster light tower and seats were added far down on the roof of the third base side, called the “Coca-Cola Party Deck”, making Fenway Park’s seating capacity just under 40,000. The “Bleacher Bar” was constructed under in center field, giving patrons a year-round restaurant that looks onto the field, and 800 new seats were added to the “State Street Pavilion”

In 2009 the seats above the far right

field grandstand were increased.

In addition all the seats were

removed from the grandstand behind

home plate and the original Fenway

Park concrete base structure was

refinished and weatherproofed with

replacement seating installed in the

lower bowl. In 2010,

the

concrete in the left-field seating

bowl, which was built in 1934, was

repaired and waterproofed and a new

Home Plate Deck was unveiled at the

top of the grandstand behind home

plate.

In 2010, the Boston Red Sox unveiled a bronze statue of "The Teammates" outside Fenway Park, just a few yards from the statue of Williams. Sox players Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio were Sox teammates for seven seasons, all served in World War II, and were friends for a lifetime. In 2013 a statue of Carl Yastrzemski, acknowledging his last at bat, took it's place in the gallery.

In 2010, Fenway Park was the busiest it had been in quite some time. Major events at the park started on New Years Day, when the NHL Winter Classic was played between the Philadelphia Flyers and the Boston Bruins. After a week of other skating events a college hockey doubleheader, dubbed Frozen Fenway, was played at the park. 2011 marked the final year of improvements to the ballpark. Included were the installation of three high definition video boards and scoring system. The lower right field stands were repaired and waterproofed with new seats installed, as well as the refurbishing of the 1934 wooden grandstand seats.

Since its construction, Fenway Park has hosted 20 soccer matches. The first game was played on May 30, 1931; 8,000 fans were on hand to see the New York Yankees of the American Soccer League beat Celtic 4–3. The Yankees goalkeeper, Johnny Reder, would later return to play for the Boston Red Sox. During 1968, the park was home to the Boston Beacons of the now-defunct North American Soccer League. In July 2010 Fenway hosted an exhibition game between European soccer clubs Celtic Football Club and the Sporting Club of Portugal in an event called "Football at Fenway". A crowd of 32,162 watched the two teams play to a 1-1 draw Another match took place in 2012, between Liverpool Football Club, an English Premier League club owned by the Fenway Sports Group, and AS Roma, an Italian Series A club. The match ended in a 2-1 win for AS Roma before a crowd of 37,169. Then, in 1914 AS Roma defeated the Liverpool Football Club, 2-1, with Michael Bradley of the United States scoring the first goal in the exhibition soccer match.

A total of 212 former players, arriving on the field from various parts of the ballpark, sauntering to the position they played when they were in Boston to celebrate the 100th birthday of Fenway Park on opening day of 2012. Jim Rice was the first former player to enter the field, from the tunnel underneath the left-field grandstand to his position in left field. Dwight Evans was next, emerging from under the center-field bleachers and strolling to right field. They were followed by first baseman Bill Buckner from canvas alley, third baseman Frank Malzone from left field, second baseman Jerry Remy from center, shortstop Rico Petrocelli from canvas alley, center fielder Reggie Smith from left field, pitcher Jim Lonborg from center and Carlton Fisk from the Sox dugout. The fans stood and cheered every single player, whose picture and Boston playing dates were shown on a screen to the left of the main video board, which was showing them as they entered the field.

They all had one thing in common: each was wearing their Red Sox jersey, some bright white and others yellowish, depending upon the era in which they had played. Hugs were shared by players of the different generations. A short time later, Fisk, Rice and Yaz lined up to catch ceremonial first pitches from Boston Mayor Tom Menino with Thomas Fitzgerald and Caroline Kennedy, the great-grandchildren of John "Honey" Fitzgerald, the man who threw out the ceremonial first pitch in 1912. At 69-93, the 2012 Boston Red Sox were the worst baseball team to take the field at Fenway in almost half a century. It was a performance so staggering that fans and commentators were often at a loss for words. The Sox managed to destroy themselves with injuries, infighting and completely horrible play. New manager Bobby Valentine, who was supposed to restore order after the disarray that marked the collapse of 2011, proved to be an unmitigated disaster who only added to the dysfunction. It was a year many would like to forget, but that would all change in 2013.

The 2013 Red Sox was a team that wasn't supposed to win. After all, most of the players from the 1912 team were returning. As a result, there were questions at every position but they played as a team, with a different player contributing every day. In the end, it was the leadership of new manager, John Farrell, who had been Terry Francona's pitching coach, they came from worst to first, achieving the best record in the American League with eleven walk-off come-from-behind victories. At the center were the veterans David Ortiz, Jacoby Ellsbury, Clay Buchholz, Jon Lester, and Dustin Pedroia. The additions of Mike Napoli, Stephen Drew, David Ross, Jonny Gomes, and Shane Victorino anchored, what came to be, a team that loved and supported each other and the city of Boston. Fueled by the Boston Marathon bombings, the team became a group that acted as the central point of the city's healing. With the "617 - Boston Strong" jersey hanging on their dugout wall for every game, they continued their inspiration play throughout the playoffs and the World Series, winning the first World Series championship at home, in front of their fans. It was a feat that had not been done since the 1918 Red Sox.

In 2015 the Red Sox unveiled some improvements starting with a the new Gate K (for Kids), with the new Kids Concourse, where there’s a 6-foot-9 Wally the Green Monster bobblehead, an interactive video wall for fan photos and a children’s activity area. Also were added 174 new seats. The State Street Pavilion added 112 additional seats, the bleachers with 28 new seats and a 34-person party suite called the Infiniti Suite was added on the EMC Level.

On November 21st, college football returned to Fenway as Notre Dame hosted Boston College. It was the first time a football game was played since the Boston Patriots hosted their final home game in the AFL against the Cincinnati Bengals on Dec. 1, 1968. Even though the game was played in Boston, it was officially a Notre Dame home game as part of its Shamrock Series, an annual game that Notre Dame hosts in venues across the country. Notre Dame beat Boston College, 19-16.

Hurling was played the next day, for the first time since 1954, in an exhibition match between Galway and Dublin. Galway won it, 50-47, with a madcap flurry of late goals that erased the 36-31 lead Dublin carried into the fourth quarter. High School Thanksgiving Day football also returned to Fenway Park in 2015, for the first time in 80 years. In February, 2016, the Polartec snowboarding and freeskiing U.S. Grand Prix tour event, "Big Air" came to Fenway Park. A 140-foot high snow ramp, taller than the light towers at the ballpark, brought in athletes from around the world including Olympic and World Champions. Prior to the baseball season Fenway underwent some changes. Per a league mandate, after a fan was struck in the head by a shard from a broken bat and seriously injured in 2015, protective netting was installed between both dugouts. Virtual reality booths made fans more interactive, making it feel like the fan was on the field with the players during batting practice. The booths became a part of the kids' areas known as "Wally's Clubhouse", the "Kids Concourse" and the Budweiser Right Field Roof Deck. A new bar named the "3rd Base Saloon" was also added.

On the field, the 2016 Red Sox left everyone with a bittersweet taste in their mouth. After winning the 2013 World Series, the team did a two-year stint in the AL East basement but wound up on top of the division, an impressive leap and one that proved to be their only legacy in 2016. The Red Sox ended up having the most powerful and prolific offense in baseball behind stellar performances not only from young guns, Mookie Betts and Xander Bogaerts but also from a 40-year-old David Ortiz in his final season, and Cy Young Award winner, Rick Porcello. After the 2016 season, "Pesky's Pole" (the right field foul pole) was taken down and renovated. Several rows in the back of the right field grandstand were removed and a new bar named "Tully's Tavern" was constructed. A new video board replaced the space occupied by the "Cumberland Farms" sign in right field. The virtual reality station in the "Kids Concourse" was expanded with a VR Batting Cage. And the right field wall in front of the bullpens was replaced with a removable wall to better accommodate non-baseball events.

On July 15, 2017 the Boston Red Sox and the Red Sox Foundation honored

Vietnam War veterans and their families at Fenway Park, with a number of

special events, including the eighth annual Run to Home Base and the

Moving Wall memorial displayed outside Fenway.

Craig Kimbrel was every bit as dominant as Sale. Simply making contact against Kimbrel was a victory for opposing hitters. Not only did Kimbrel have power, but he also had impeccable control. He whiffed nearly half of the batters he faced (126 out of 254). In 2017, the depth of both the home and visitor’s dugouts was increased by moving the front rail of the dugouts forward 3 feet. Before the 2018 season, expanded safety netting and dugout-style seating were among the improvements made. The new dugout seats gave fans a view similar to the players by attempting to recreate the dugout experience with bats, helmets and a giant Gatorade cooler. The new protective netting was extended beyond the dugouts. All 30 major league teams had extended protective netting for the 2018 season after a series of incidents where fans were badly injured after being struck by balls and bats.

The Sox swift exit from the first round of the playoffs in 2017, for the second year in a row, made winning in the regular season seem somewhat unimportant. It would be advancing in the post season that would show the team's true ability. The firing of manager John Farrell was one reaction to losing in the first round of the playoffs, and the hiring of Alex Cora was the response by Dave Dombrowski. The signing of J.D. Martinez made the Sox offense the most powerful in the majors. He and Mookie Betts dominated most of the offensive batting stats in 2018. Martinez won the "Hank Aaron" Award for being the best hitter in the league while Betts won the Most Valuable Player Award. On August 17, 2017 Red Sox owner John Henry pushed to have "Yawkey Way" reverted back to it's original name of Jersey Street. On May 3, 2018, the city of Boston officially renamed the street "Jersey Street" one again. The 2018 Red Sox season was one that was never seen before. The Sox not only conquered everyone they saw, they crushed them, winning their fourth championship in fifteen years. They romped to a 17-2 start, won 108 games in the regular season and went 11-3 in the postseason, dispatching the 100-win Yankees and the defending champion 103-win Astros, before putting away the Dodgers. There was nobody left. The Red Sox stood on top, alone with 119 total wins, making them one of the greatest baseball teams in history.

On November 13, 2019 the Houston Astros, admitted that they employed an intricate system for stealing signs in 2017. In the middle of all this was Red Sox manager, Alex Cora, who was then the bench coach for the Astros and accused of creating the system. On January 14, 2020 the Sox released Cora, who would later be suspended by MLB. On March 12, 2020 MLB and the rest of the world stopped and went into quarantine, the result of the Coronavirus pandemic. Finally a 60 game schedule was put in place and the season commenced in late July. The Sox, like every other team, would be playing in an empty ball park without the motivational effects of Fenway fans to spur them on. The Sox finished in last place.

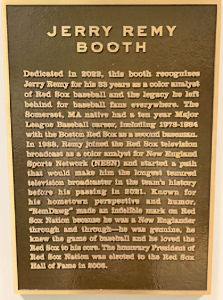

The Red Sox bounced back in 2021 and took the American League wild card by beating the Yankees in a one game playoff. But tragedy struck at the end of the year, as beloved broadcaster Jerry Remy lost his battle with lung cancer. In 2022 the NESN broadcast booth was named after him and they also built a studio above the right field bleachers with terrace seating, named "Truly Terrace", where the pre and post game broadcasts would originate from.

For the fifth time in 11 years, the Red Sox finished in last place with a record of 78-84 in 2022. The Sox were awful against AL East opponents going 25-50 and 52-34 against everyone else. In June they played great ball, with a 20-6 record, but they collapsed and fell below .500 by the end of July. In 2023 it was no different for the Sox as the team finished in last place for the third time in the last four years.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)