HOW THE RED SOX FORCED THE BOSTON BRAVES TO LEAVE TOWN ...

|

|

|

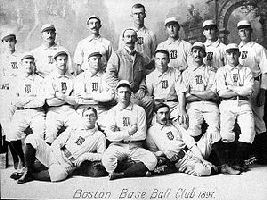

1897 BOSTON BEANEATERS |

In the early 1900s, the Boston Beaneaters were the National League team on the other side of those tracks owned by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, that separated the Huntington Avenue Grounds from their ballpark, the South End Grounds. The Beaneaters were one of the league's dominant teams during the 19th century, winning a total of eight pennants.

The Beaneaters had many of the biggest stars. There was catcher, Mike "King" Kelley, outfielders Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy, who were known as the "Heavenly Twins" because of their gracefull play in the field.

In 1892, the league played a split schedule, crowning the winners of each half of the season. The Beaneaters beat the Cleveland Spiders for a convincing 5-0-1 win in the best of nine series.

The team was decimated when the American League's new Boston entry set up shop in 1901. Many of the Beaneaters' stars like Cy Young and Jimmy Collins, jumped to the new team, which offered contracts that the Beaneaters' owners didn't even bother to match. They only managed one winning season from 1900 to 1913, and lost 100 games five times.

The original team nickname of the National Leaguers was the Red Stockings in 1871, then Red Caps in 1876 and Beaneaters in 1883. When the team again changed their name from the Beaneaters to the Doves in 1907, they abandoned the color of their red stockings also. Boston Americans owner, John I Taylor jumped on the opportunity to steal the team’s original name and colors. Hence, the birth of the name Boston Red Sox.

|

|

|

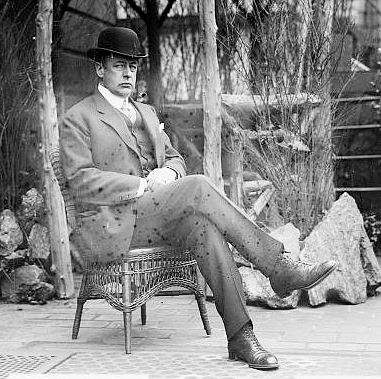

JAMES GAFFNEY |

Another nickname change to the Rustlers in 1911, did nothing to change the National League club's luck, as they continued to have losing seasons. The team finally became the Braves for the first time in 1912. Their new owner, James Gaffney, was a member of New York City's political machine, Tammany Hall, which used an Indian chief as their symbol. Instead of the old English “B” on their uniforms, the Boston team now sported the profile of a proud Indian.

The new owner wanted a new ballpark also. The Red Sox were building a new park and the

South End Grounds had been around for twenty years and needed serious work. The original park was called

Walpole Street Grounds and went through three incarnations starting in 1876, leading to the present configuration. Opening in 1894, the second renovated park was the only double-decked ballpark that Boston had ever had. In addition to the six conical fanciful “witchers’ caps” from

which, pennants waved in the breeze. The actual interior had a semi-circular grandstand called the Grand Pavilion. It was a more of a majestic theatre where Sir Lancelot would have felt at home seeing a jousting tournament.

Sadly, this magnificent pavilion was short lived, set ablaze a month after it opened, during a game between the Beaneaters and the Baltimore Orioles, by kids playing with matches under the grandstand. The

fire destroyed the park in just one hour, and spread to the wooden tenements in the neighborhood, surrounding the field. Before it ended, the “Great Roxbury Fire” consumed 164 wooden buildings and left 1000 families homeless. The owner, Arthur Soden had underinsured the park and

it could not be recreated. Valued at $75,000 it was insured for only $40,000.

|

|

|

SOUTH END GROUNDS |

The Beaneaters moved to the old Congress Street Grounds while the park was rebuilt. It reopened a month later on June 20, 1894 in a smaller somewhat disappointing cheaper configuration, becoming one of the most notoriously small and cramped parks in all of baseball. Failing to find the proper site, Gaffney decided to renovate the old downtrodden park, enlarging the grandstand and tearing down the left field bleachers.

In 1912, as the Red Sox marched their way to a championship in their new ballpark, the Braves lacked pretty nearly everything that goes to make a good ball club. Their captain, Bill Sweeney batted .344 and Jay Kirke hit .320 but that was it. Best of the pitchers was Hub Perdue, who had a 13-16 record. But in New Bedford of the New England League they found a young acrobatic phenom. Late in the season they brought up their future star and future Hall-of-Famer, Rabbit Maranville to play shortstop. Maranville was small in stature, but with a large personality. He was known as one of baseball’s most uninhibited clowns and practical jokers.

Under new manager George Stallings, the Braves of 1913 showed some life. They started the season in last place and started climbing out of the cellar and by September they moved into fifth place and finished there. It was the highest they had reached in eleven seasons.

In

1914, the Braves put together one of the most memorable seasons in baseball history. They started by picking up second baseman

Johnny Evers from the Cubs in February, followed by third baseman Charlie Deal

and outfielder Red Smith. After a dismal 4–18 start, the Braves seemed to be on pace for a last place finish. They lost games, but they had the spirit of winning and not quitting. On July 4, 1914, the Braves lost both games of a doubleheader to the Brooklyn Dodgers. The consecutive

losses put their record at 26–40 and the Braves were in last place, 15 games behind the league-leading New York Giants, who had won the previous three league pennants. After a day off, the Braves started to put together a hot streak, and from July 6th through September 5th, the Braves went 41–12. Chasing the New York Giants, the Braves moved up the standings. Pitchers

Dick

Rudolph, Bill James and

Lefty Tyler served a steady stream of goose eggs and recorded eighteen shutouts. In mid-August the Braves went into the Polo Grounds and won three straight. A week later they tied the Giants for first place. The Braves then took a doubleheader from the Cardinals, and

Lefty Tyler followed that up with a no-hitter. On

September

2nd,

Rudolph and

James took a doubleheader in Philadelphia and the Giants

lost to Brooklyn, giving the Braves a one game lead for the first time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

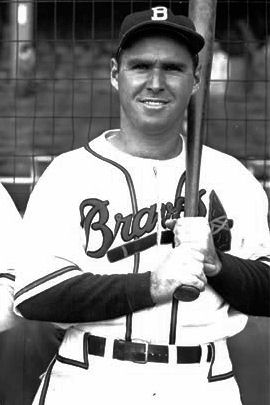

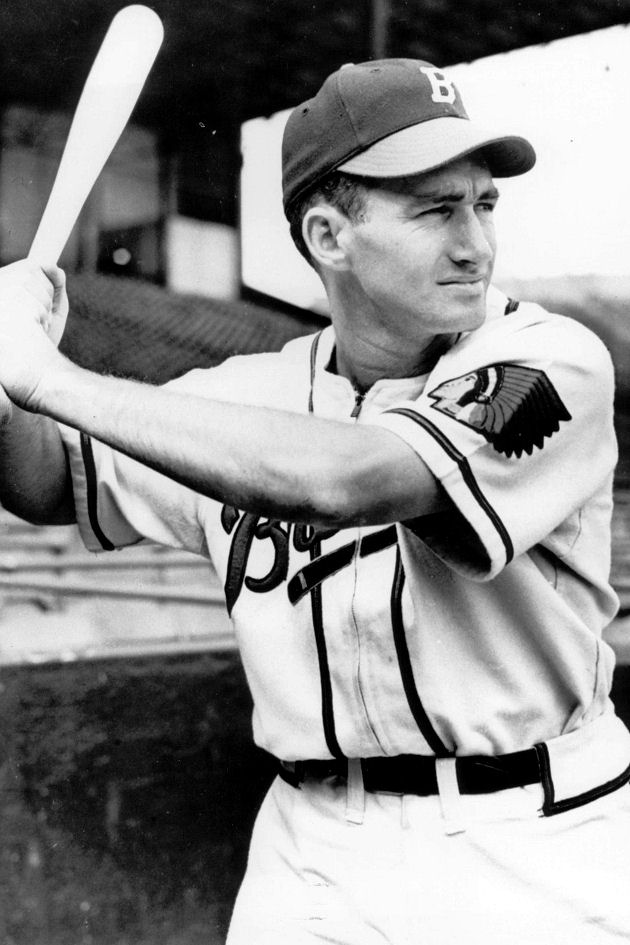

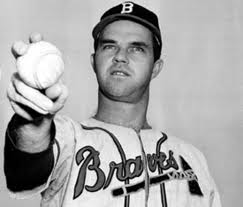

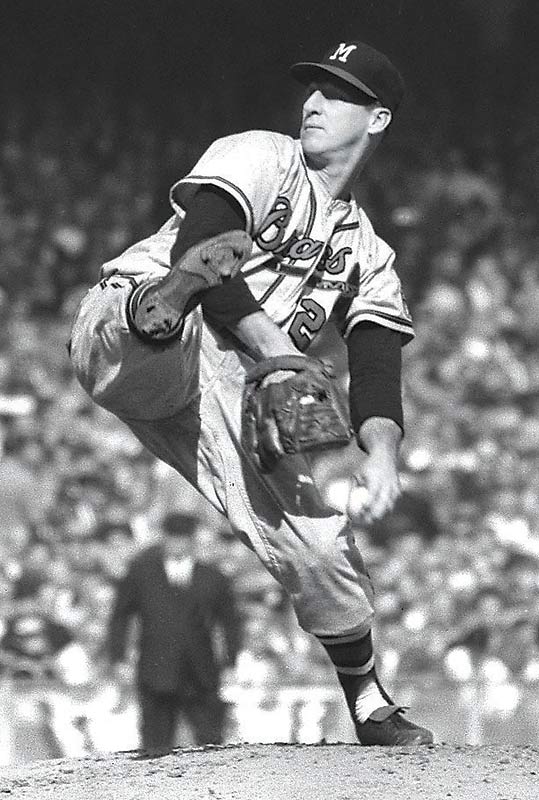

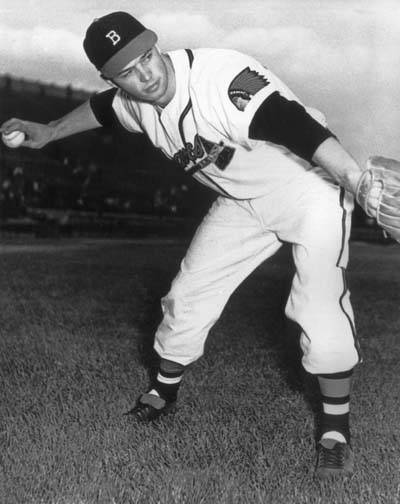

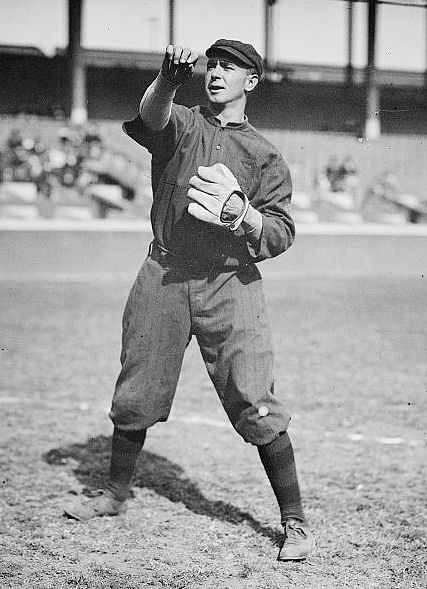

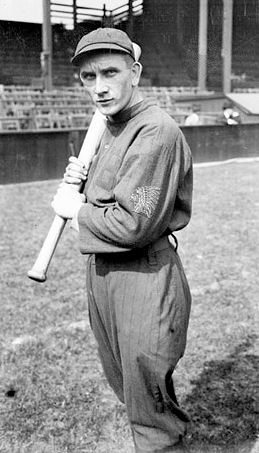

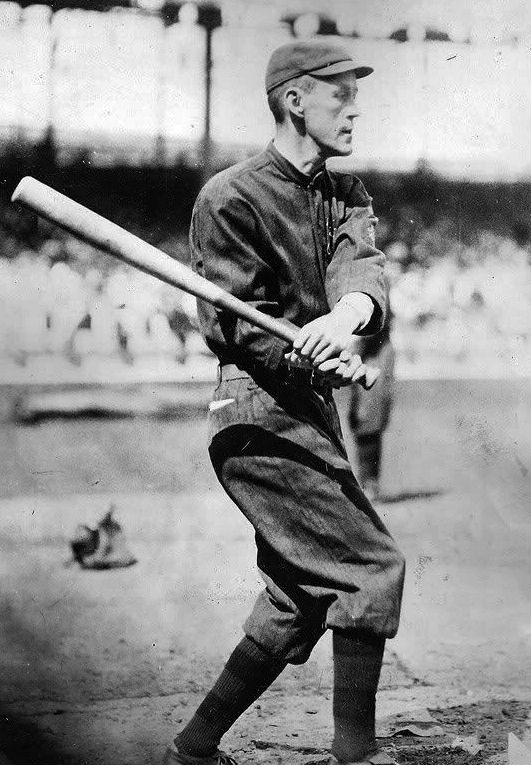

BILL JAMES |

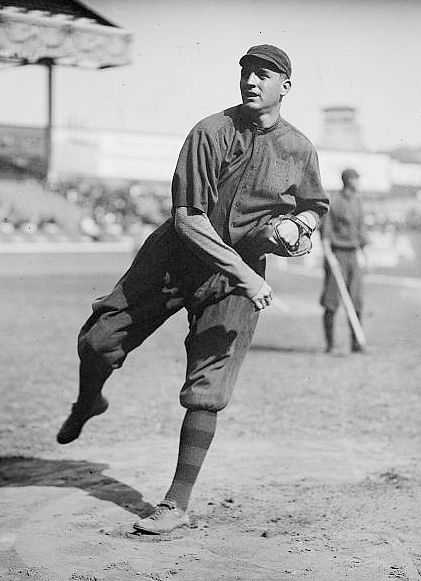

DICK RUDOLPH |

MARANVILLE |

JOHNNY EVERS |

LEFTY TYLER |

Red Sox new owner Joe Lannin graciously offered the use of Fenway Park for the remainder of the season starting with a crucial Labor Day doubleheader with the Giants. On

September

7th the

Braves set a new attendance record at Fenway Park, drawing 74,163 fans for both games. In the first game, the Braves mounted a ninth inning walk-off comeback against Christy Mathewson, and then crushed the Giants 10-1 in the night cap. The next day

Bill James pitched a 8-3 three hitter

and the Braves were in first place to stay. Stallings kept the Braves hustling. The Braves tore through September and early October, closing with 25 wins against six losses, while the Giants went 16–16. They won the pennant by 10 ˝ games over the

second place Giants and were dubbed the “Miracle Braves”.

Bill James had won twenty-six games to lead the league. He won 19 out of his last 20 with a 1.90 ERA.

Dick

Rudolph finished with a 27-10 record.

Johnny Evers won the league MVP, and

Rabbit Maranville was

runner-up. Despite their amazing comeback, the Braves entered the World Series as a heavy underdog to Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's. Nevertheless, the Braves swept the Athletics - the first unqualified sweep in the young

history of the modern World Series.

|

|

|

BRAVES FIELD |

Because the Braves were allowed to finish the 1914 season at Fenway Park, the success and huge attendance numbers inspired owner Gaffney to finally build a modern park. Gaffney had found the site he wanted on Commonwealth Avenue on the old Allston Golf Club. The park was built for $600,000. The lot was big enough, so that Gaffney built what he considered the perfect ballpark. Gaffney built the park on the back of the lot on Commonwealth Ave and by doing this was able to sell the frontage at a handsome profit. Groundbreaking took place March 20th.

The Braves played at Fenway Park again in 1915 until Braves Field was ready. Moving to the new ballpark from the South End Grounds was like moving from a modest three room apartment into a nineteenth century mansion.

Gaffney wanted to build a perfect ballpark large enough so that a home run could be hit inside the park in any direction. It was perfect for its era. In 1915, baseball was a game of hit and run, not home runs. The walls and fences of Braves Field were purposely distant and out of a batter’s reach. Compounding the challenges that batters faced there, the wind caromed off the river and blew infield (sometimes bringing with it a shower of coal dust from the railroad yard just beyond the outfield fence).

For years, the only home runs hit there were indeed, inside-the-park jobs, not counting a few flukes, such as when a ball went through an open slat in the scoreboard or bounced out of play in fair territory (which counted as a homer then). Indeed, the first two home runs hit over the right field wall didn’t come until 1917 and 1921—both hit by the same player, Walton Cruise (first with the St. Louis Cardinals, next with the Braves). And nobody hit a ball over the left field wall until the New York Giants’ Frank Snyder in May 1925—almost 10 years after the park opened.

But when the Braves traded away young slugger Shanty Hogan, most of the home run balls that landed in these new seats were hit by opponents. So in the middle of the 1928 season, the Braves tore down the stands. Thus began a just-about-annual cycle of tinkering with the dimensions of the park. Over the years the “perfect ballpark” had many configurations trying to make the field more hitter friendly, but nobody could figure how to move eight million pounds of cement stands closer to the field.

|

|

|

GEORGE STALLINGS |

The grand opening was on August 18th. Dick Rudolph won a rare game by beating the Cardinals 3-1, before 42,000 fans. It was the largest park in the majors at the time, with 40,000 seats, and a very spacious outfield.

The park was novel for its time as a trolley car line spur off Commonwealth Ave brought fans right to the park. The major event for the Braves in 1915, was the opening of the new ballpark. The Braves pennant defense was unsuccessful. While the Philadelphia Phillies won only ninety games, the Braves finished in second place, seven games behind. The Phillies won 14 and lost 7 to the Braves. Bill James was not the same pitcher nor was Dick Rudolph, and they didn’t have a .300 hitter on the team.

In January of 1916, Gaffney sold the Braves at a huge profit. That year the Braves made a better fight for the pennant and were in first place as late as September 4th. They ended up trailing the pennant winning Brooklyn Robins by only four games. In 1916, the Red Sox won the American League championship and played the World Series at Braves Field against the Robins.

|

|

|

JOE OESCHGER |

After contending for most of 1915 and 1916, the Braves only twice posted winning records from 1917 to 1932. Aside from Rabbit Maranville the Braves didn’t develop any significant new talent for years. The Braves continued to play baseball the way it was played in the pre Babe Ruth era. While other teams concentrated in obtaining home run hitters, the Braves, because of where they played, continued to play hit and run baseball, and they therefore continued to lose.

In 1923, the great event of the season was shortstop Ernie Padgett’s unassisted triple play. One of the most exciting things that happened at Braves Field was a 26-inning game that saw Joe Oeschger of the Braves and Leon Cadore of the Dodgers both pitch a complete game—and that ended in a 1-1 tie. The May 1, 1920, contest stands as the longest ever.

But fans didn’t want to see 26-inning pitching duels. They wanted dingers. Attendance at Braves games had already dropped precipitously in the late 1910s as just down the street, the Red Sox were racking up pennants.

A mere four years after opening the park to a record-setting overcapacity crowd of 42,000, the Braves finished the World War I shortened season of 1918 in seventh place (in an eight-team league), having drawn a mere 84,938 for the season. In 1918 the Braves were again sold to a New York group headed by a friend of New York Giants manager John McGraw named George Grant. Boston fans could not help but wonder if the Braves would become an unofficial farm team of the Giants. Grant owned the team but it was still Gaffney who owned Braves Field.

Hopes for the Braves grew somewhat in 1921. The Braves were floating around the first division and stayed in third place until September. From 1922 thru 1924 the Braves lost 100 games each year, and George Grant lost interest in his team. Grant’s buddy, John McGraw brokered a new marriage.

|

|

|

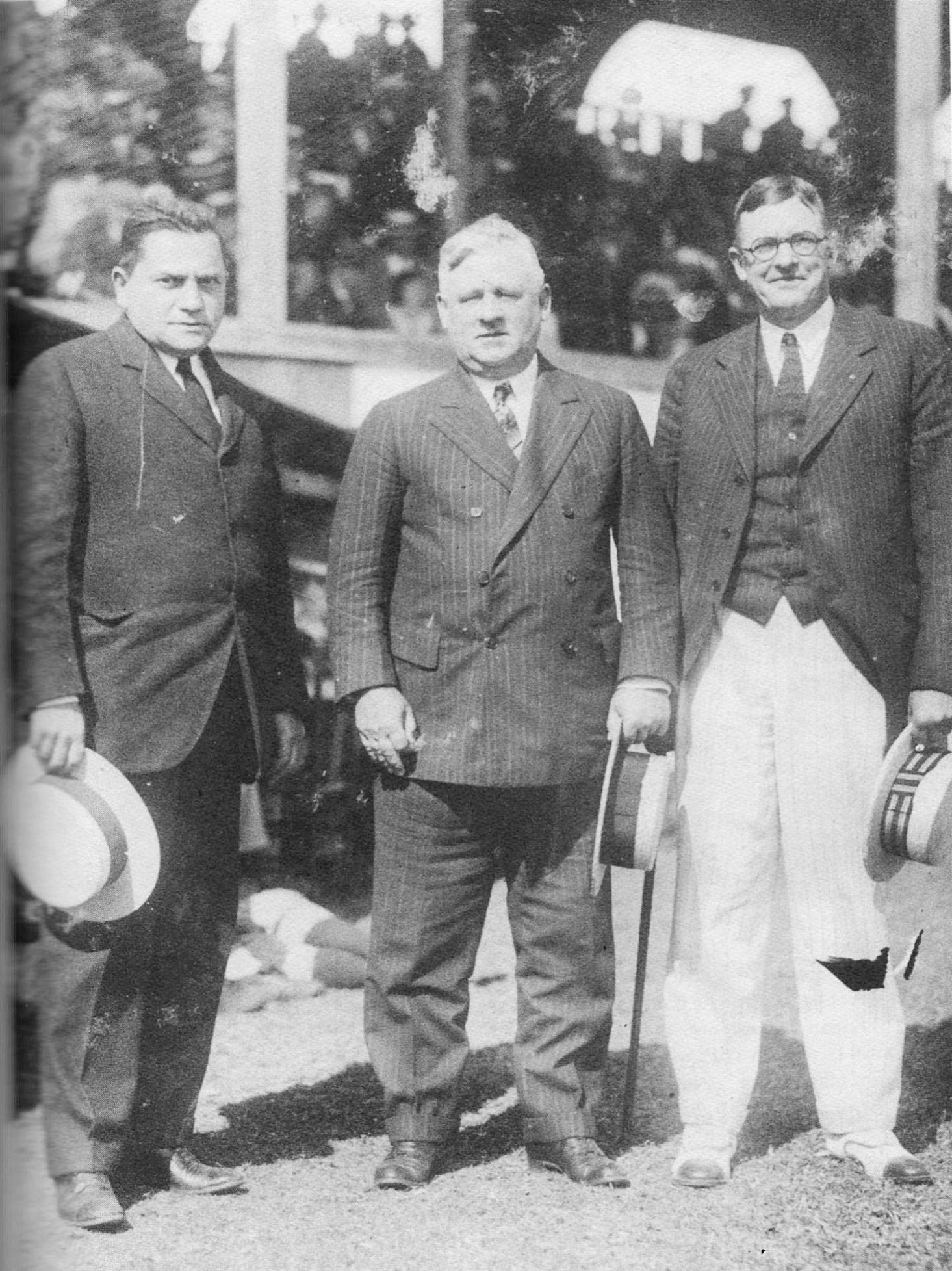

JUDGE FUCHS, |

The team would be sold to former deputy attorney general for the state of New York, Judge Emil Fuchs. Fuchs jumped at the opportunity. He would buy the Braves on one condition, and that was having Christy Mathewson run the team so he could continue his law practice. In 1923, Fuchs, Mathewson and New York banker, James McDonough bought the Braves. Boston fans were not surprised that the team was still controlled by New Yorkers. Judge Fuchs and not Christy Mathewson made the biggest impression in Boston. In the thirteen years Judge Fuchs would own the Braves, the Braves would experience more bizarre events that left fans dazed. At the center of every event was Judge Fuchs. Fuchs saw the opportunity to bring fans into Braves Field.

When Christy Mathewson died suddenly in 1925, Fuchs took over team operations and hired Dave Bancroft as manager, and when the team failed to win, Bancroft was fired and the Judge decided to manage the team himself.

Judge Fuchs was a fan, one who tried to be an owner, tried to manage the team, finance the team, and be the head of public relations. He brought Sunday afternoon baseball to Boston and promoted his team through a “Knot Hole Gang” for young boys and frequent “Ladies’ Days” at Braves Field. The Judge was a sucker for charities and a stooge for those with political ambitions. He made friends with the baseball writers. He threw lavish parties for them and consulted them on baseball decisions. His two favorite people were Christy Mathewson and Ed Cunningham, the sports editor of the Boston Traveler.

|

|

|

THE JURY BOX (BRAVES FIELD) |

In 1926, the right field bleacher section (capacity 2,000) earned the nickname the “Jury Box” one day, when a sportswriter noticed there were only 12 fans sitting in it.

In 1926 the left field grandstand burned down at Fenway Park. There was no money to rebuild it. With the Red Sox near bankruptcy, Judge Fuchs started taking action in 1927. First was the ballpark. He had bleachers built to ring the outfield, shortening playable territory by 70 feet. Unfortunately, by mid June the opponents had hit twice as many home runs into the new stands, than did the Braves.

|

|

|

ROGERS HORNSBY |

In 1928 the Judge acquired Rogers Hornsby to be the club's player-manager. At the plate Hornsby was a success winning the National League Batting Crown with a .387 average to lead the league, and setting a modern day Braves record. However, it did not translate into wins on the field, as the Braves finished in seventh place with a 50-103 record. Hornsby was hard to get along wit, so after the season the Braves decided to part ways with him.

The following season, the Judge just decided to manage the team himself. After all, he figured the team couldn’t do any worse. Well, they could and they did. They finished in last place for the first time in six years. That was enough for the Judge. The day before the World Series started, he stepped down and hired Bill McKechnie to be the new manager. In 1929, the stock market crashed and down Commonwealth Ave, the Braves were on the move.

In 1930 Judge Fuchs found a young star in Wally Berger. Berger hit 38 home runs, setting a club record and a record for rookies that stood until 1987. Other young stars, not recycled veterans, made their way onto the Braves roster. Unlike the Red Sox, Fuchs and McKechnie were gradually building a good team.

|

|

|

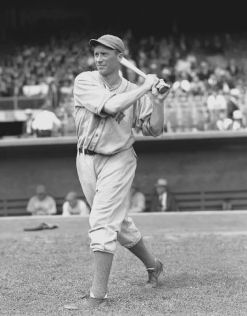

WALLY BERGER |

In 1931 the Braves posted their 10th straight losing record finishing in seventh place with a record of 64-90, and then in 1932 the Braves showed some promise. They started out fast, but lacked the staying power. The Braves finally managed to be competitive in 1933. Wally Berger had 27 homers, was batting .313 and was invited to play in his first of four All Star games. Later in the year tragedy struck the Braves as their only superstar, Rabbit Maranville broke his leg sliding into home, thus ending his twenty-four year career. Without him to anchor the infield, the Braves had trouble, but they did manage to finish a respectable fourth.

But down in Kenmore Square an event happened that would eventually seal the fate of the Boston Braves. In 1933, the Red Sox along with shabby Fenway Park, was sold to thirty year old, Tom Yawkey.

By 1934, with Tom Yawkey buying the Red Sox and rebuilding Fenway Park, Fuchs, knew he didn’t have the money to compete with the millionaire. He knew with a brand new Fenway Park, he would have trouble putting people in the stands.

He made a nice profit the last few years, but spent it as quick as it came in. He wanted the National League to bail him out, but it would be difficult to get the other club owners to provide help during the depression. He was desperate. Just before the December winter meetings, Fuchs put a bizarre plan into action. The Braves' owner announced that there would be greyhound dog racing at Braves Field. Fuchs had applied to the Massachusetts Racing Commission for a license to conduct dog racing at his ballpark.

Since gambling and baseball do not mix, Fuchs needed the Braves to play their home games at Fenway Park. The Red Sox had suffered through the worst decade in their history. The Red Sox were not going to do anything to help their only competitor for Boston’s depression era baseball dollars. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey's response was brief. "Over my dead body."

It was the "Depression" and Yawkey was spending money and picking up star ballplayers from teams who were in financial trouble. Looking for a way to get more fans and more money, Judge Fuchs worked out a deal with the New York Yankees to acquire Babe Ruth, who had started his career with the Red Sox and the Judge thought would be a curiosity, pulling people away from the Red Sox and putting them in the seats at Braves Field. Fuchs made Ruth team vice president, and promised him a share of the profits. He was also granted the title of assistant manager and was to be consulted on all of the Braves' deals. Fuchs even suggested that Ruth, who had long had his heart set on managing, could take over as manager once McKechnie stepped down.

| . |

|

|

|

BABE RUTH |

At first, it appeared that the Babe was the final piece the team needed to compete with the Red Sox in 1935. On opening day he had a hand in all of the Braves' runs in a 4–2 win over the Giants. However, that proved to be the only time the Braves were over .500 all year. Events went downhill quickly. While the Babe could still hit, he could do little else. He was so big that he couldn't run, and his fielding was so terrible that three of the Braves' pitchers threatened to go on strike if the Babe were in the lineup. On May 25th, Babe hit three home runs against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He should have quit right there. The next day he struck out four times. Finally the Babe realized he was being used as a sideshow attraction. It was obvious that he was vice president and assistant manager in name only and Fuchs' promise of a share of team profits was hot air. In fact, the Babe discovered that Fuchs expected him to invest some of his money in the team. The Babe retired from baseball on June 1st. A few months later the Judge was unable to meet his financial obligations. It was the end of his dream. He stepped down as president and later filed for bankruptcy.

On the last day of 1935, the Braves partners brought in Bob Quinn to run the team. It was Quinn who owned the Red Sox in the 1920s and ended up selling the team to Tom Yawkey. The Braves finished 38–115, the worst season in franchise history. Their .248 winning percentage is the third-worst in baseball history, and the second-worst in National League history (behind only the 1899 Cleveland Spiders). Through it all, Wally Berger tore it up, leading the league with 34 homers and set a Braves record with 130 RBIs. Even Rabbit Maranville made a comeback and played twenty games.

|

|

|

BILL McKECHNIE |

In 1936 the Braves changed their name to the Bees, and the former Wigwam became the Beehive. The name change didn’t help, the Bees remained a second division team and a joke.

The Bees couldn’t even do the All Star game correctly. The 1936 All-Star game was played at Braves Field (now National League Ball Park). Even this was a minor disaster, as a miscommunication with the media led to erroneous reports that the game was sold out. The result: 25,000 fans sat in a 40,000-capacity stadium while stars like Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Leo Durocher, and 1936 Rookie of the Year Joe DiMaggio played on the field. The name change lasted until 1941.

At the end of the 1937 season, manager, Bill McKechnie, was named manager of the year by the Sporting News. He used the opportunity to leave town and manage the Cincinnati Reds.

By the late 1930s, the Red Sox rebuilding was complete. Bob Quinn was desperate to do something, and put a bandage on his problem. He decided to hire a friend of his, Casey Stengel, to manage the Bees. Stengel was not yet the manager he would be leading the Yankees in the 1950s. As the Bees (or Braves) manager from 1938 to 1943, he was better known as a comical character than as an effective leader.

|

|

|

CASEY STENGEL |

In 1941, as Ted Williams raced toward .400 the interest was in Kenmore Square, not up on Commonwealth Ave. The next year Judge Fuchs picked made some moves he hoped would improve the team and lure fans. The first was Ernie Lombardi, who would lead the National League with a .330 batting average. Another was outfielder Tommy Holmes, who batted .278, along with veteran Paul Waner and pitcher Jim Tobin, a pitcher well suited for the vastness of Braves Field. He would pitch two no-hitters two years later. But the team finished in a miserable seventh place in 1942.

A new owner, construction magnate Lou Perini, bought the team in 1943. Along with his partners Guido Rugo and Joe Maney, the trio was known as the “Three Little Steam Shovels”. The partners were not baseball men, they were business men with grand ideas. But the big thing they had to contend with now was World War II and a lack of a talent pool to draw from. The team again finished in sixth.

|

|

|

LOU PERINI |

Perini was business smart. He saw what Yawkey had done, and he too went after stars from other teams. In 1945, Perini closed his first major trade in getting Cardinals’ ace pitcher, Mort Cooper. The team finished in sixth yet again, but their young star, Tommy Holmes batted .352 and finished second in the NL batting race, scored 125 runs with 224 hits and led the league with 28 home runs and 47 doubles. His major feat was a 37 game hitting streak, during which he batted .423 It was the longest modern day streak in National League since 1897. As the season ended, Perini made another good move. He hired Billy Southworth to manage the team by throwing a lot of cash at him. Southworth would prove to be the best manager the Braves had at the helm in a very long time.

During the 1946 season, with the World War II over, baseball was king. It represented normalcy and attendance at major league ballparks skyrocketed. It was time for Perini to make his move. The Braves made fourteen deals for players. Perini bought slugger Earl Torgeson in from Seattle. He was followed by Alvin Dark, one of the best college players in the country. Pitcher Johnny Sain came back to the team, fresh out of the Navy.

Young Johnny Sain had made his debut with the Braves on April 24, 1942, in relief, giving up a walk and a wild pitch in 1 2/3 innings of a 3-1 loss to the Giants at the Polo Grounds. Even with the war on, Sain was able to complete the season. Upon receiving his draft notice, he had enlisted for aviation training in the Navy on August 21st. However, he didn’t have to report until November 15, whereupon he was sent to Amherst College along with fellow big-league inductees from the Red Sox, Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky.

Showing no signs of rustiness after a three-year layoff, Sain became a star pitcher and the Braves’ ace in 1946. He turned in a 20-14 slate, a career-best 2.21 ERA, and a league-leading 24 complete games for the Braves, who took a big leap to 81-72 and fourth place under Billy Southworth. But the Red Sox won the American League pennant and were going to their first World Series in twenty years. Perini knew that he was 10 years behind and late to the dance. The battle was uphill. In 1946, Boston was all about the Red Sox.

|

|

|

BILL SOUTHWORTH |

Perini fought hard for the Boston baseball dollar. Even with the success of the Red Sox , life was improving for the Braves. Tommy Holmes was an effective contact hitter. Bob Elliott, a hustling, hard-hitting team player, and four time All Star, was acquired from the Pirates over the winter and won the Most Valuable Player Award in 1947. Elliott would hit over twenty home runs four times in a Braves’ uniform.

And there was a decorated war hero, a southpaw who would be the perfect complement to Johnny Sain and a number of other pitchers over a long career – The winningest left hander in baseball history, Warren Spahn. First signed by the Boston Braves before the 1940 season, Spahn reached the major leagues in 1942 at the age of 20. He clashed with Braves manager Casey Stengel, who sent him to the minors after Spahn refused to throw at Brooklyn Dodger batter Pee Wee Reese in an exhibition game. A decorated war hero, Spahn served in the army for three seasons and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. In 1947, Spahn led the National League in ERA while posting a 21–10 record. It was the first of his thirteen 20-win seasons.

The Braves were the first to install lights and it paid huge dividends, as night baseball became a huge success. They drew close to one million fans, setting their all time attendance record. Perini also contracted with Boston College to play their football games at Braves Field. Overall, the season was a very inspiring.

In 1947, the Braves started a charity called “The Jimmy Fund”

after Braves players visited a boy simply known as “Jimmy” at

Children’s Hospital in Boston. Jimmy's story began in 1948 when Dr. Sidney Farber's 12-year-old

lymphoma patient, Einar Gustafson, the original "Jimmy", was an

inspiration to hundreds of thousands of people. Gustafson was selected to speak on Ralph Edwards' national

radio program, "Truth or Consequences," which was broadcast from the boy's

hospital room on May 22, 1948. During the broadcast, Edwards spoke to the young cancer patient from

his Hollywood studio as Boston Braves baseball players, Gustafson’s

favorite, surprised him with a visit to his hospital room. The show ended

with a plea for listeners to make donations, so Jimmy could get his own TV

set to watch his beloved Braves play. Not only did he get his wish, but

more than $200,000 was collected and the Jimmy Fund was born.

When the Braves moved to Milwaukee, the Red Sox picked up the

torch and it burns strongly to this very day.

BOB ELLIOTT

1948 was the greatest year in Boston's baseball history. Braves owner, Lou Perini had come full circle. In four years he had done what it took Tom Yawkey a decade to accomplish with the Red Sox. Now, both the Red Sox and

Braves were in the pennant race.

Alvin Dark who hustled, with grit and determination becoming the Braves' leader winning “Rookie of the Year”.

Bob Elliott had clutch hits with 100 RBIs and 23 home runs.

Eddie Stanky got everything hit at him at shortstop and

Sibbi Sisti stepped in

without missing a beat when

Stanky got hurt.

Tommy Holmes not only batted .325 but threw in some great defense down the stretch, saving games by throwing out runners in tough situations.

Stanky had a blend of youngsters and veterans and was able to get the most out of all

of them.

But it was the pitching of

Warren

Spahn and

Johnny Sain that took the Braves all the way. Sain went 24-15, making him a twenty game winner for the third consecutive season. Over Labor Day, the Braves swept a doubleheader, with

Spahn

throwing a complete 14-inning win in the opener, and

Sain pitching a shutout in the second game. Following two off days, because of rain,

Spahn came back the next day and won, and

Sain won the day after that. Three days later,

Spahn won again.

Sain won the next day. After one more

off day, the two pitchers were brought back, and won another doubleheader. The two pitchers had gone 8–0 in 12 days' time. Hence the expression “Spahn and

Sain, then pray for rain”.

Perini had done it and built a winner. The Braves grabbed first place won the National League

pennant in 1948.

TOMMY HOLMES

ALVIN DARK

EDDIE STANKY

JOHNNY SAIN

WARREN SPAHN

In 1951, with the Braves floundering in fifth place,

Tommy Holmes, who was now manager of the Hartford farm team, was called back to Boston to manage his old team. He also remained on the active roster as a pinch hitter. It was hoped he could arouse the club, and bring

fans back to Braves Field. But the team went 48–47 under Holmes for the remainder of 1951, and when they began 1952 with a mark of 13–22,

Holmes

was fired on May 31st and replaced by Charlie Grimm.

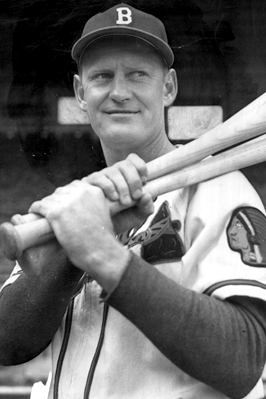

A powerful young rookie named Eddie Mathews proved to be one of

the only bright lights for a bad baseball team. Mistakes

compounded mistakes and the Braves finished seventh, drawing

only 281,000 fans, with only two days where attendance passed

10,000

EDDIE MATHEWS

Lou Perini saw the writing on the wall. He estimated that staying in Boston would cost him $1 million per year. These were the days before television contracts. Boston could not support two teams

at the gate, and his was not the better of the two.

Over the winter

Perini developed a secret plan to move the team, an act that had been unheard of in baseball. But with airplane travel replacing days on the road via the railroad, it was now possible to move a team away

from the east coast. On March 18, 1953 after receiving unanimous league approval,

Perini took the Braves and left forever to Milwaukee. There the Braves had their AAA affiliate, Milwaukee Brewers, also owned by

Perini and a brand new stadium waiting for them, totally financed by

taxpayer dollars. Boston now belonged to the Red Sox.

It was a rocky and interesting ride over the years since the 1914 Miracle Braves shocked the baseball world by coming from last to first and winning the World Series and the 1948 Braves coming so close.

Interestingly enough, after the Braves left, the Red Sox began

a downhill slide. In the 1950s

Yawkey

had no competition to push him. He didn’t have a team

full of stars anymore and the Red Sox headed downhill and

became a losing team. Their stars got old and retired.

All that was left was

Ted Williams and the farm system produced only mediocre players. The fans just stopped showing up to see a team that never finished less than 11 games out

of first place at the end of the season. Fenway Park became deserted, and Yawkey now lost money.

But a thousand

miles away, in an area with a booming economy and growing rapidly, Milwaukee and the Braves attracted fans from all over the midwest, shattering attendance records with over two million fans attending games each year after the move. The Braves were a phenomenal success on and off

the field. The Braves had made over $34 million dollars in Milwaukee since leaving Boston. In 1955, Milwaukee hosted the All Star Game, and it was there that the Dodgers' Walter O'Malley and the Giants' Horace Stoneham saw the Braves success, and realized the huge

profits to be reaped in a new untapped post war suburban market.

In 1957 as the Dodgers and Giants moved to the west coast, in Milwaukee, behind

Warren

Spahn, Eddie Mathews, and a youngster named Hank Aaron, the Braves would finally again bring home another World Championship.

But from there it was financially downhill.

Perini's greed and a mediocre team alienated the Milwaukee fan base and they stopped supporting the team in the early 1960s. The Braves lasted only 13 years in Milwaukee before being drawn to Atlanta in 1965. Atlanta simply offered a

better and more lucrative deal in an untapped geographic market with no competition. Lou Perini sold the Braves in 1962, but for better or worse, he changed the sports world. Moving from Boston, he opened a door that still has profound effects on today's sports

landscape, where owners can play geographic regions off each other, seeking the sweetest and most profitable deal available.

Now the Braves sat back and watched the Red Sox claw their way toward another American League title. It

all came down to the one game playoff at Fenway Park that went to the Indians,

and hopes of a subway series with the Braves faded away. Now

Boston belonged to the Braves for the time being.

he 1948 World Series, which the Braves lost in six games to the Cleveland Indians, turned out to be the Braves' last hurrah in Boston. In 1949, the Braves slumped and the Red Sox came close with another shot

at the pennant, losing to the Yankees on the final day. The magic was gone at

Braves Field.

Johnny Sain hurt his arm and continued to pitch.

Eddie Stanky and

Alvin Dark were traded to the Giants.

Earl Torgeson got hurt and

Billy Southworth became ill.

.jpg)

BRAVES FIELD LAYOUT @ NICKERSON FIELD

(Boston University)

.jpg)